U.S. Steel Guides Operations and Sales with Real-Time Process Information to Maximize Cash Flow

Only a few years ago, the typical process control article on control/information technology (IT) integration talked about the traditional separation of the two functions, the resulting rival factions, the difficulties of making the connections, and the problems with turning process control data into useful decision-making information.

More recent articles, along the lines of this issue's cover story, describe advances in integration technologies and software that are easing connectivity and helping end users sift real value from process control data.

Those kinds of articles focus on how control and information systems can be brought together, with little attention to why. This story is different. This article presents a remarkable example of why business systems really need plant floor information and how such information can make a critical difference to the company's success. The example is one of the most asset-intensive, margin-driven, besieged-by-foreign-competition industries of modern times: steel.

The DuPont Theory

To improve business performance, real-time process information must be used for more than feeding sexy dashboards that make managers and executives feel important"it must drive timely decisions that increase profitability. The importance of real-time information can be understood from the DuPont theory, which in essence says to maximize profits, maximize return on assets:

Profit/Assets = Profit/Sales x Sales/Assets

The theory proposes that return on investment (here simplified to profit/assets) is the main performance criterion. Plant performance can be improved by analyzing activities that affect profit/sales and sales/assets, and weaknesses can be recognized by comparing a company's performance of those activities both within its facilities and industry, and with other companies in other industries.

Manufacturing companies have traditionally used dollars per unit, or tons in the case of U.S. Steel, as the common metric to measure profitability. Most plants have a good understanding of their profit/sales, or margin. For example, U.S. Steel has always had highly detailed information about exactly what it costs to make any one of its more-than-5,000 products. "We knew our costs down to pennies for chemistries, gauges, widths," says Vas Shapkaroff, financial analysis manager, U.S. Steel, Gary, Ind. "We had a highly sophisticated system for cost per ton."

But sales/assets, or turnover, includes a time element: How fast can sales be generated? How fast can the plant produce? "It is very difficult for us to understand how you can manage your return on assets"-really know your business"-unless you know both those ratios really well," says Michael Rothschild, founder and CEO of Maxager Technology (www.maxager.com). "You cannot solve the profit problem just by knowing your margins. You must know your profits over assets"-the speeds that materials move through the plant. Companies know it on an overall level"-quarter by quarter"-but not in sufficient detail.

"You need to take process control information about how fast material goes through the highest-cost, lowest-capacity points in the plant"-the bottlenecks, the most capital-intensive choke points"-bring that data in to financial analysis, and do dynamic pricing. The data exists, but it is not part of conventional financial analysis."

U.S. Steel managers were convinced a better understanding of time would give them better visibility into their business and enable them to accelerate cash flow and drive profits up. "We've known for a long time that what we really sell our customers is time on our mills," says Paul Kadlic, executive vice president, sheet products. "We also knew that if we could price and manage this time more effectively, we could offer customers more value and make more money at the same time."

Analysts at U.S. Steel knew that despite the powerful financial and managerial databases used to support the company's accounting, sales, and production efforts, the dimension of time or velocity was missing.

Think Velocity

Almost all capital-intensive manufacturing companies face the same problem. Traditional measurement systems don't give them visibility into the most critical dimension of their operations, the velocity at which their costly production facilities are generating cash.

Wal-Mart understands this very well. Turnover is the focal point of its strategy. It concentrates on fast-moving stock and prices it accordingly, generating profits with high volumes and very low margins.

In manufacturing, the principle is the same, but the problem is much more complex. Along with dynamic costs, such as raw materials and energy that can vary widely and rapidly, every plant has rate-limiting steps, or bottlenecks, that determine how fast a given product or product mix can be produced. These, too, can change on a daily or hourly basis as different products arrive at equipment that goes in and out of service due to setups, maintenance, or repairs. As a result, the rate that a given order generates profits is far more complex than a simple profit/sale margin can indicate.

U.S. Steel sought a way to analyze and incorporate real-time turnover information into its business systems and selling strategy. In December 1999, after researching available software products, it settled on enterprise performance management (EPM) technology from Maxager.

"We had static costing plus process control and factory system data from a three-month period," says Shapkaroff. "We loaded it into the system and ran it." The result could be expressed as a chart similar to Figure 1, where various products are represented by different-colored disks.

Figure 1: PROFIT VS. CASH

It takes real-time process information to track the rates at which

products are generating cash. Products in the lower right quadrant

can be "hidden winners."

Products in the upper right quadrant are obvious winners, with above-average margins and cash-generation rates, and products in the lower left quadrant are obviously weak. The interesting products are in the lower right quadrant, which have below-average margins but above-average cash generation. These would typically be identified by conventional accounting standards as weak on the basis of their margins, but they have potential for generating significant cash flow. Rothschild calls them hidden winners. "If the plant is not completely loaded, you must look at these products," he says. "Sell more hidden winners."

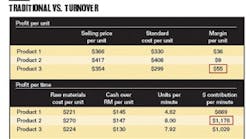

Table 1 compares the profit per unit of product to the profit per unit of time for three example products. Looking only at margin, most plant managers would be inclined to prefer orders for Product 3. "In the traditional approach, Product 3 looks like the product to push, and if the customer were to offer a large order for Product 2 if you'd come down on the price, you wouldn't do it," says Rothschild.

But when you consider how fast the product goes through the plant, it turns out Product 2 generates cash faster, Rothschild says. "It's counterintuitive unless you're a production person who knows that Product 3, which looks like we're not making much money on, that we might want to outsource or move production to China, is the one that paid the tuition for his kid's college education.

"And how low could you take that price? If you have a lot more than three products, it's not obvious. Companies with thousands of products, hundreds of customers, many facilities with various legacy systems, volatile material costs, etc., can't do this calculation on the back of a napkin.

"The profitability of an order is often baked in before the order reaches the plant," Rothschild continues. "If the profit is not there, it can be almost impossible to turn that order profitable. So it is really important to understand the profitability when the deals are being made."

Real Time Also Impacts Operations

Shapkaroff championed implementation of the real-time system in 2000. "We put a marketing, sales, and financial team together, started implementation in January 2000, and had it up and running in May, including hardware, software, and connections," he says. "We now have about 150 active users."

U.S. Steel has used the real-time information to:

* Train salespeople to dynamically price spot and contract orders to maximize cash.

* Contract smarter by limiting commitment on low dollars-per-minute products to three to six months.

* Rationalize and substitute products for win/win profit opportunities with customers.

* Work with customers to tweak their processes to use products that are lower cost for them, higher velocity for U.S. Steel.

* Provide key information at profit meetings.

* Align their commercial and operations team toward improved cash generation.

* See production difficulties.

* Learn which orders to walk away from and how to win new opportunities they really want.

* Spot low-velocity products and look for ways to improve or drop them (Figure 2).

Figure 2: SPOT THE PROCESS PROBLEMS

In this case, the strip mill products with the lowest cash-generation rates

were primarily those with particularly difficult widths

The system continues to supply U.S. Steel sales, marketing, and production managers with the information they need to win business and allocate production capacities more profitably.

"Information from Maxager has enabled our sales representatives to identify new product and pricing options available so we can satisfy our customer needs, remain competitive, and drive higher cash contributions at the same time," says Jim Kutka, vice president, commercial, sheet products. And U.S. Steel is continuing to find new ways to leverage the information. Kutka adds, "Our strategy is to shift our product mix toward products with a higher profit-per-minute so we can make significant improvements in cash flow and overall profitability.

"Gretchen Haggerty, senior vice president and treasurer, adds, "Within the first full quarter of deployment, the profit per minute information revealed by the Maxager system enabled U.S. Steel to make changes that we believe increased cash flow by millions of dollars."

The system generates payback in other ways than dynamic pricing and bidding. It has a production module that can measure production downtimes based on profit impact so manufacturing teams can more efficiently prioritize activities. The turnover information can lead to new and more effective incentive systems that align sales goals and production efforts.

"Good information has a way of making itself felt all over an enterprise," says Shapkaroff. "We're now using cash-per-minute data at five major sales offices and three manufacturing plants, and every day we're finding new and better ways to apply it. Maxager is our information change agent."