Now the convergence of business need, improved technology and a couple of decades of experience has narrowed the gap. The Holy Grail is visible on the horizon, but most companies are still a long way from integration Nirvana. The way forward is getting easier, but it’s still fraught with complexity and the perils of wrong paths taken. Culture wars and internecine squabbles over turf issues can still derail plans.

So why bother? Because the plant floor contains vital information executives need.

Bob Mick, vice president of emerging technology at ARC Advisory Group, pegs visibility and the need to synchronize operations and business activity as the drivers. Manufacturers need “to get ops more closely linked with demand, and get suppliers more coupled with operations as well,” he says.

Yves Dufor, director of production and performance management at Wonderware, says, “Globalization has rather tipped the balance and made plant-floor/enterprise integration a necessity.”

Vivek Bapat, senior director of solutions marketing at ERP giant SAP adds, “The typical manufacturer has to deal with 20 or 40 plants, some of which they own and some of which they don’t. They have to coordinate all those activities. They need to synchronize orders with execution. They need to coordinate effectively across distributed manufacturing plants.”

Finally, the relentless pressure on executives to cut costs and turn a profit is driving the need for plant data. Peter Martin, vice president of Performance Management for Invensys concludes, based on interviews Invensys has done with more than 1,400 executives over the last 15 years, “Almost universally one of [executives’] top issues is that they don’t know where they are making or losing money in manufacturing operations on a minute-to-minute basis. They know at the end of the month, but by then it’s too late.”

But simple need alone isn’t enough to make plant-floor/integration happen. Technological and cultural barriers remain.

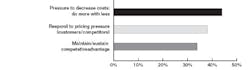

FIGURE 1: BUSINESS DRIVES AFFECTING MANUFACTURING INTELLIGENCE STRATEGIESWhy Is This So Hard?

One reason may be that, in the past, manufacturers were asking the wrong questions. “For the last 30 years, we’ve been focused on integration without solving business problems,” says Martin. “Now we’re transitioning to solving business problems.”

The actual integration, while not a trivial exercise, has been doable for decades, he adds. “We’ve been able to connect this stuff since 1975. It’s easier and cheaper now, but if all you’re doing is connecting IT to automation and not solving problems differently or better, it adds no value.”

Martin Michael, vice president of business solutions for systems integrator Advanced Automation, agrees that many companies have put the cart before the horse. “To be successful at this kind of integration, you should never answer the technology question first. The business goals should come first; then approach integration and technology issues. Any data that doesn’t advance business goals is useless.”

Having that clear business case creates another advantage—beyond the obvious one of making the project easier to sell to the bean counters. It may cut the project down to a manageable size.

Michael counsels, “Break the project up into the business modules needed to solve a specific project. Build a road map. Get some early wins.”

That’s been the strategy at Coca-Cola Amatil (CCA), the largest Coke bottler in Australia. CCA began with connecting Activplant’s Insight for Microsoft Excel manufacturing intelligence system to the bottling lines across several plants to get information about bottling rates and line capacity—by no means a full-blown enterprise to plant floor connection. The project began in 2003 with a pilot project on one bottling line at the Sydney facility, says Wayne Luxford, a CCA manufacturing analyst (See Figure 2).

The reason for the implementation was simple: “We have a convoluted [bottling] line, and it was hard to spot issues,” explains Luxford. “It runs 24/7, and the engineering support works mostly during the day. It was a matter of just not knowing what was going on. Often there would be arguments about what the problem was. Now, once we have the data, we can prove where the problem is. We can smooth out all the starts and stops.”

Activplant’s Insight for Microsoft Excel for Microsoft Excel manufacturing intelligence system has helped manufacturing analyst Wayne Luxford increase the time between bottling line stoppages from 2.5 minutes to 7 minutes at the Coca-Cola Amatil bottling plant in Sydney, Australia.

The result? “We’re running our lines at seven minutes between stops now, as opposed to 2.5 minutes before,” says Luxford. That doesn’t sound like a lot, but at 480 bottles a minute 24/7, those numbers add up fast.

CCA has rolled Insight for Microsoft Excel out on all the lines at Sydney and to facilities in Brisbane and Melbourne, and in the next 18 months will ditch its outdated ERP system for a new SAP model. Only then it will be ready to start sending information such as scheduling from the ERP to the plant floor and finished goods reports back up to the inventory planning department and the warehouse for aid in managing stock.

The Networking Problem

In spite of successes such as CCA’s, there is real concern on the plant-floor about any integration that connects its systems with the rest of the enterprise.

William Hawkins, WBF board member and principal at HLQ Ltd., a fieldbus and batch control consultancy in St. Paul, Minn., states the plant floor’s chief objection to integration with enterprise systems. “Manufacturing and business have different areas of competence, and there’s little overlap. In that sense, business is a hazard to manufacturing because the people don’t have background and training. Even if you’re just reading stuff, you can bring a system down,” he says. “As far as manufacturing is concerned, IT is a hacker, because they don’t have a concept of safety. They don’t think about it, so they don’t include it in their concepts.”

While this problem is real, it’s not unsolvable; it’s just that the solution is counterintuitive, says Julie Fraser, principal with manufacturing consultancy Industry Directions. “You need separate networks. This is a bigger problem than it used to be because now we have the same technology [on the plant floor] as the rest of the operation. IT wants to standardize. They want one big happy network, but there’s no such thing. To get the best out of this [integration], you actually have to separate the two systems. The trick is to create the handshake between them. Now we have the technology to make it happen in ‘near-real time.’”

Dennis Brandl, president of BR&L Consulting and another WBF board member, recommends one of two solutions. “Best practices call for a segmented network with a firewall between [the plant and the enterprise] or a ‘demilitarized zone (DMZ).’ ”

The DMZ consists of two separate networks—one for the enterprise and one for the plant floor. Each network has its own firewall and between them are one or more servers. “On that dedicated server, you have historians, MES systems, databases, etc., and you can’t get directly between the two,” explains Brandl.

The Reagans Canada Ltd. plant in Bradford, Ont., maker of lubricants, stabilizers and polymers for PVC, uses just such a walled-off architecture to connect its Siemens-based MES to the enterprise. The system was installed when the mandate came down from corporate to double production without adding staff. To get that done, management needed visibility into orders, raw material availability, production scheduling, and plant performance.

“The MES is the interface between the ERP and the plant floor. We also want to integrate it with RFID for inventory, with the lab and SCADA systems, and with the plant historian,” says Enrico Valle, Reagens Canada’s computer service manager. “It’s running on its own machine, but uses the same network as the rest of the plant,” he adds. “We did it that way to make it simple. Reagens has a virtual private network (VPN) on the corporate side, and all of it’s connected via Ethernet. We use industrial switches and hardware. We built in redundancy with double wiring and double switches. The ERP side is strictly regulated by the IT department. My department regulates the MES and plant floor.”

In addition, each side has its own firewalls and security procedures and proxy servers. “We keep it in pretty strict isolation,” says Valle.

Culture Clash

Perhaps the harder nut to crack before we complete the journey is the cultural issue. While not everyone may feel as strongly as Hawkins that “Business people don’t think much of engineers because engineers want to do it right, and MBAs want to do it cheap,” the fact remains that there is a big language gap between the two. This gap is not only between the humans trying to arrive at a workable solution to their problems, but between the systems they’re using to do it.

ERP systems are about transactions and accounting. They use the old total-at-the-end-of-the-month paradigm. Plant-floor systems are about real-time monitoring and control. If the ERP systems aren’t designed to cope with real-time information, it’s also true that the plant-floor systems aren’t designed with financial databases in mind.

“Control works with a physical model,” explains Dr. J. Patrick Kennedy, president and CEO of OSIsoft. “That’s a scalable model.” To add more capability, all that’s required is “more iron,” he says. “But most integration works off a product or process model. I don’t care about temperatures, but tons, volumes, etc. That can be fairly ambiguous, and [business] processes get changed all the time.”

At this failure-to-communicate level is where technology has finally caught up with the promise over the last few years to make integration easier. Software advances, such as extensible markup language (XML), simple object access protocol (SOAP), and, most pertinently, batch-to-manufacturing markup language (B2MML) have simplified writing the integration software necessary to make connections between plant and enterprise applications.

All of the major plant-floor system vendors—GE Fanuc, Emerson Process Management, Siemens, Invensys/Wonderware, Rockwell Automation, ABB—and even some smaller vendors like Citect (now owned by Schneider) and Iconics—have developed architectures to enable easier data transfer between various parts of the plant floor and between the plant floor and the enterprise. At the same time, ERP vendors are reaching out to make linking to the plant floor easier.

Just last month, Invensys released two SAP-certified applications for process and packaged goods manufacturers that can be plugged into existing industrial automation systems to provide interoperability between them and SAP enterprise software.

SAP and ABB worked together to build the XML-based interface between its ERP and advanced planning and optimization (APO) applications and ABB’s manufacturing execution system (MES) at German papermaker Steinbeis Temming. Orders flow from the ERP system to MES for production optimization and control, and data about goods movement and order progress goes back to the ERP for dispatch and invoicing. The link “enables us to track every individual batch,” says Hans-Gerd Lachmann, Steinbeis Temming’s IT manager.

Other major ERP vendors are also making overtures to the plant. Oracle has been one of the leading supporters of Open Applications Group Inc. (OAGi) since its inception, and has supported the Open Applications Group Interface Specification (OAGIS) scenarios and business object documents within its Oracle E-Business Suite. Microsoft’s .NET initiatives and its rebranded Dynamics line of ERP systems targeted at specific industries are also easing some of the connectivity challenges, especially for smaller operations. All of the big ERP vendors are also paying close attention, and in some cases, actively participating in developing the standards that are enabling integration success stories.

Standards Issues

The ISA88 and ISA95 standards are important builders of the bridge across the plant-floor/enterprise divide. ISA88 deals with the control and process engineers’ view of batch processes. ISA95 looks at data on the next level of the stack: the operational views of interest to plant supervisors, production managers and operators.

“We’ve made good progress in connecting the MES layer to the enterprise,” says Keith Unger, principal manufacturing IT consultant for systems integrator Stone Technologies, and a member of the ISA88 and ISA95 committees. “We’ve done some excellent implementations through OPC. We defined equipment and how it needed to operate. ISA88 is bottom up and ISA95 is top down. We’re hoping to meet in the middle.”

In short, says Unger, the back office says, “Please produce these products using these materials,” and the plant responds, “This is what we actually produced.” What ISA95 does is provide the common language to enable that communication to take place.

Of course, there’s still a long way to go. The standards themselves aren’t complete, and education is still a big issue.

At a recent tradeshow, Advanced Automation’s Michael asked attendees at a presentation how many of them were familiar with ISA88. “A lot of them couldn’t identify it. ISA88 and ISA95 are moving this forward, but it’s a challenge even when organizations are cooperating. How do you educate folks down in the plant? Clearly, if companies want to get broader adoption, they have to do more on education further down the food chain.”

Where Are We Now?

Manufacturers have come a long way on this plant-floor-to-enterprise integration journey. Big companies especially are pushing toward the final goal. Operations unwilling or unable to make the leap to total integration are looking at manufacturing intelligence solutions to gain better information about their production processes to solve particular business problems—even if utimately someone has to hand-deliver that information to the executives.

The biggest challenge is still change management, says OSIsoft’s Kennedy. “Process people don’t want you messing with the process, but they’re going to have to share data with the business, or the business won’t be there.”

MES or Manufacturing Intelligence—Applications in the Middle

MES has always been the red-headed stepchild of manufacturing software. OSISoft president and CEO Dr. J. Patrick Kennedy says, “MES may still be an acronym in search of an application. I don’t think there’s an MES package. I understand fully what control systems do. I understand ERP, but I don’t have this clarity with MES. It’s the name for the work that has to go on between the control system, owned by the plant, and the ERP system. There are hundreds of things that need to access both systems and count of a good cooperative relationship between them.”

Mark Leroux, ABB’s marketing manager for collaborative management systems, says, “One of the purposes of the MES layer is to consolidate information,” says “MES really combines layers zero through three of the Purdue model. It eliminates the control layer/MES boundary, and provides a seamless view of information from a factory-floor perspective.”

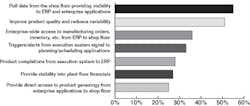

Analysts at Aberdeen Group are calling this layer “manufacturing integration and intelligence” and describing it as “a tool that enables the collection and aggregation of data from multiple sources,” that must go beyond portals and executive dashboards to “add a level of intelligence. . .and provide real-time visibility, event management and analytical tools that enhance proactive and predictive control and drive execution.”

OSIsoft’s Kennedy says, “What you’re really seeing here is business process re-engineering. Reasonable people with reasonable skill sets will define what has to be done and the processes that fall in the MES bucket. MES layers can see those processes and will end up doing the work.”

SOA—The New Kid in Town

Okay, boys and girls, get out your notebooks and write down this new acronym—SOA. That’s service-oriented architecture. It’s a new software tool that promises to make integration faster and easier. What SOA does is enable users to write little pieces of software, called “services,” to perform specific tasks. These services aren’t tied to a specific architecture or platform, which makes them an ideal vehicle for handling integration between operations and enterprise systems.

SAP’s Vivek Bapat explains how SOA works. “In the case of the plant, there’s a lot of real-time information, but it has no context. If an exception alarm occurs, you want to be able to notify the enterprise in real time, and you need to design a business process about how you transfer that information. You tell the system, ‘If this occurs, notify me right away.’ SOA enables this.”

OSIsoft’s president and CEO, J. Patrick Kennedy, says, “The SOA approach gives you the methodology to look at the value. What services do you want the equipment to provide, and what do you want to provide to customers? As you go through these scenarios, you define the service architecture for your system.”

It’s still early days yet for SOA, but software vendors are taking a serious look, and many, such as SAP, are enabling their applications to use SOA.

“Realistically, the problem is that the integration isn’t really flexible enough to keep up with the changes,” says Industry Directors’ principal, Julie Fraser. “There’s a lot of innovation at the product level, so there’s a lot of innovation at the process level, so there have to be changes at the enterprise level. In some ways, it’s a good thing that people are just starting [with plant-floor/enterprise integration]. SOA will make this way easier and more flexible. It won’t make problems go away, but may make solving them easier.”

Leaders relevant to this article: