This Control Talk column appeared in the May 2022 print edition of Control. To read more Control Talk columns click here or read the Control Talk blog here.

Greg: I remember the days of using engineering flow diagrams (EFDs), and while the latest edition of the ISA book Control System Documentation has a chapter on EFDs, the process industry has moved on to piping and instrument diagrams (P&IDs) with increasing efforts to make them smarter. To look at the evolution of the P&ID and its potential future capability, I’m joined today by Michael Stenning, a recently retired former colleague, and Gil Soucy, an instrument and electrical specialist, who will share developments at a large specialty chemical company.

Michael: Our older documents include EFDs but we have transitioned exclusively to P&IDs. The EFDs include instruments and loops and show manual valves in the piping, but the information for piping sizes, insulation and instrument ranges were all kept in separate documents, usually a pipe schedule and list and instrument lists. In our major product line, we started using smart P&IDs, of which I am a huge fan. The reason is that one document can provide nearly all motor information, all instrument information—including vendor, model numbers and instrument ranges—as well as pipe sizes and insulation information.

The smart P&ID can publish reports for all motors, all manual or air-operated valves, including the types of valves (check, ball, gate, globe, relief, etc.) and the instrument ranges, insulation reports, pipe diameters and materials of construction. I wish all companies were committed to smart P&IDs, as these reports make checkout and construction much easier. Also, the off-page connectors are smart, so one can click on them and go directly to the referenced P&ID. The smart P&ID can include "flow bubbles" on each pipeline that can be used in the process flow diagrams (PFDs). In some cases, we have included PFD information on the P&ID by importing a table (from Excel, for example) into the drawing so all information is in one place.

The PFDs include design information for flow rates for each stream, which then defines the pipe sizes that are reflected in the P&ID. It also includes ranges for temperatures, flows, pressures, pressure drop, batch sizes as applicable for reactors, weigh bins, silos, feeders, etc., and cycle times. We have not done a good job of syncing the PFDs with the P&IDs to allow information to update from one document to another automatically. The last set of PFDs I built were all done in Excel, so the information is editable and can be updated based on actual data, but I did have to ensure that the P&ID and the PFD information was consistent by manually comparing the two.

Usually, PFDs would show the ranges for flow, temperature, pressure or level, for example, that are the expected max and min values. However, these are not the instrument ranges, which is usually broader than the operating range. Ideally, the PFD should include the instrument calibration range as well as the expected operating information. One software package that could transfer information between PFD and P&ID would be very desirable.

There is an additional complication in that different sites use different software. There are not a lot of drafting resources that are familiar with using the smart software programs, so we had a dedicated E/I engineer (Gil Soucy) who took ownership of smart P&IDs. We also trained a draftsman, but the draftsman retired. As plants upgrade or change equipment, our experience has been that PFDs and P&IDs are not always marked up properly and updated, so it is almost like starting from the beginning. Our process control group had discussed transitioning to a Bentley smart P&ID software application company-wide, but those discussions were at least five years ago. Since then, there has been more downsizing, and I believe this was put on the shelf.

As with all items in the business world, we must do a better job of assigning the value that smart PFD/P&ID software can bring. In the old days, corporate engineering would build the PFDs and P&IDs. It would not be a bad thing to have this as a corporate skill to be used for all plants, then a dedicated group of engineers/drafting resources could manage new smart PFDs/P&IDs and the individual sites would not have to have these skills; they would just need the process expertise to work with these resources to maintain and develop these documents.

Gil: To answer your original question, we now use exclusively P&IDs. In the past, we generated EFDs as well as instrument flow diagrams (IFDs), where the EFD concentrated on equipment, piping, insulation, etc., and the IFD concentrated on instrumentation and electrical. It was very difficult to ensure that both of these documents were updated when changes were made. Most times, both documents were incorrect.

Michael has done a very good job in summarizing how we are using smart P&IDs. The real power, as Michael stated, is to build reports that are helpful to the construction, process and start-ups teams. Any data that is included in the P&ID can be organized into customized reports. We can publish e-stop, gauge, temperature element, thermowell and instrument lists, just to name a few. Michael has included many more. In the past, every discipline seemed to have their own spreadsheet(s) for their particular area of responsibility, but now we include everything in one document and generate separate reports from there. We also include every motor with its hp, and this becomes the basis for developing motor lists and identifying the power needs for the project.

In many cases, we include the drawing number and schematic drawing number for that particular motor and include it on the P&ID. We have also done the same with instruments, so the instrument drawing is easily identified. We have tried to make it such that the P&ID is a good index to the process and some of the supporting documentation. In creating the P&IDs, we include every I/O point. In the past, many of the I/O points were assumed. For example, in the past, when a motor was shown on the P&ID, it was assumed that there was a start, stop, jog and maybe a disconnect switch with an interlock.

With our new philosophy, every I/O point is shown. The P&ID now becomes a document that can be used to generate accurate I/O lists. We even distinguish PLC I/O from DCS I/O, so separate I/O lists can be created. With these I/O lists, we can assign the cabinets where the I/O will be located and include the file, card and address information, which is critical for our checkout documents. This has enabled us to give P&IDs to the vendors that are building our equipment and they specify everything that we require including I/O assignments.

Software for smart P&ID, out of the box, may potentially support Performance Improvement Plan (PIP) drafting standards as well as those of the International Standards Organization (ISO), International Society of Automation (ISA), German Institute for Standardization (DIN) and Japanese Standards Organization (JIS)-ISO. We are using the PIP standard, but we have had to highly customize it, since our specialty plant contains a large percentage of equipment that is not supported by PIP. Customization is fairly straight forward and the custom symbol sets can be used from project to project. Once a new symbol is created, you can assign properties to that symbol that are specific to that piece of equipment. For example, PIP does not have a symbol for a “roll,” so we have created a roll with custom properties. Now we can state whether the roll is smooth, laser engraved, grit blasted, etc. We can also show whether it is an idler, tendency or driven. We also include roll diameter, length, etc. With this custom symbol, we can then create roll lists including all of the properties. We also include vendor name, so we can provide vendor specific lists.

We started using smart P&ID software around 2009. Since that time, the product has evolved. We are not using the 3D portion due to staffing issues. In the past, I would create the P&IDs with the help of the process engineers and a draftsman, and the mechanical engineer would create the 3D model of the process piping, equipment, etc. These were separate documents. The newer software can create 3D models of the process from the P&IDs and vice-versa. I am sure it would be an extremely powerful tool, but we have not had the resources to implement it.

As you can see from the above descriptions, our use of P&ID has really centered around producing good construction documents. The smart P&ID software we use does not have any of that functionality. As a matter of fact, we have even considered not showing how instruments interconnect on the P&IDs, because we are never certain what control schemes will be utilized by the process engineers, and we don’t want to have to update P&IDs every time the control scheme is changed.

The way that the smart P&ID software we use works, you create the drawing, and as the drawing is created, you fill in the data and this populates the database. You can also go back at any time and add to the data. This allows you to create the basic flow diagram and add more and more detail as the design becomes formalized. I have heard that one of the other smart P&ID companies uses just the opposite method. You first build your database, then pick from the database to create the P&IDs. I can see this as being useful in the way that we start a project. First, we create the equipment information summary (EIS) and this could become the database for the P&IDs. This would also eliminate the problem, where once changes are made to the P&IDs, the EIS needs to be updated separately.

Michael: I'd like to add a few other comments. The P&IDs are the beginning of the process for defining what kind of process control algorithms need to be used, but do not describe them. Usually, we will add notes and define interlocks, sometimes some process actions that imply the kind of PID control or sequencing is required. Usually, a process engineer and a process control engineer collaborate together to describe how the process should operate and what the key controls need to be. Are we doing feed forward control? Or, indicating what kind of data smoothing or filtering needs to take place. We end up with either a written process control description or a series of flow charts to define how the controls should be configured. These are then reviewed and approved by all parties before actual coding starts to take place.

One other thought is that in these days where manufacturing sites are audited for ISO compliance, a change in process control logic or loop parameters should be properly documented in operating procedures and operating conditions. And, if these result in P&ID or PFD changes, they should also be modified at that time. I am not sure all of these documents are included in ISO audits—but they should be. This would prevent documentation from becoming obsolete, but it does require resources to do this. There are layers to the auditing process so there is a concern how well documents are updated that are not included in an ISO audit. We have management-of-change processes that should catch this, though history would indicate we do a lousy job of monitoring them.

Greg: Smart and smarter P&IDs can make innovation easy and easier, giving smart and smarter process control improvements. Let’s all hope that when the guy who really knows what is going on retires, we are not left in the dark.

(Courtesy of Michel Stenning, Gil Soucy, and Hector Torres)

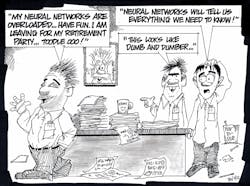

10. Why keep constantly updating the engineering drawings if things will keep changing anyways? We’ll deal with all changes after mechanical completion.

9. Cannot find that little black notebook where I used to keep track of all changes… where could it be?

8. Who needs accurate engineering drawings?

7. We have had this same set of drawings for 30 years now, they must be OK.

6. Where are my marked prints?

5. The control folks can deal with this outdated rev, up to date drawings are overrated.

4. Updating documents is at the bottom of my priority list. Management has moved me onto a new higher valued activity.

3. Was that napkin really the only copy of that drawing we had?

2. They completed construction using revision 1 of the drawing. Unfortunately, the current drawing is revision 7.

1. When you are deep into construction you realize most of the drawings are stamped “Undeveloped Design, Field Fabricate.”