By Nancy Bartels, managing editor

Like the man says, its the best of times and the worst of timesfor automation professionals anywayand its going to be that way for decades to come. Thats the conclusion of a survey of 163 Control readers and conversations with the some members of our editorial board.

We asked nine questions, all focused on the general issue of what process automation will be like in 10 to 20 years. Among our readers, while we found a fair amount of FUDfear, uncertainly and doubttheres also a good bit of optimism about the future.

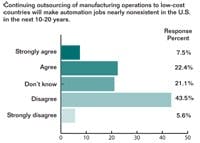

Outsourcing is still the Monster under the Bed in manufacturing, and therefore, in process automation. A full 30% of those surveyed say they think the outsourcing of manufacturing operations will make automation jobs nearly non-existent in the U.S. within 20 years. Another 21% say they arent sure. With 67% of companies outsourcing professional and engineering services last year, according to Controls June Salary Survey (See Payback Time, p. 43, June issue) the concern is hardly an idle one.

OutsourcingHow Big a Threat?

Those surveyed are divided on the question. Just under half (49.1%) dont think outsourcing will kill off the process automation profession in the U.S. , but a full 30% think it will, and another 21% arent certain.

Manufacturing is not all going to move to China, says Dan Miklovic, research vice president at Gartner Inc. and Control editorial board member. Were going to see a shift of a lot to other parts of the world, but at the same time, weve discovered that the world is a dynamic place. As soon as the energy costs went through the roof, [weve seen] that economically it now makes more sense to do some manufacturing here.

Don Allen, vice president of corporate communications for Incuity Software thinks we can handle the outsourcing threat. He said in his response to the survey, While I see individual roles changing, I think the U.S. will become more competitive again in the global economy. The low cost labor of other countries wont be as significant a factor. Itll get back to being smart about manufacturing and making sure the entire enterprise is well run.

As Miklovic sees it, the problem is not one of cost, but of supply. A lot of the design and engineering will move to other places because we just dont have enough people here. Theres an engineering shortage here, and people will go other places to get the automation skills they need, he says.

Young people here in the U.S. just dont enter the field like they did in the past. Part of the reason, beyond the general sense that manufacturing doesnt offer the opportunities it once did, is that many young engineers dont understand the value of automation engineering. They all want to write software, says editorial board member Larry Wells of Georgia-Pacific.

He adds that over the years, manufacturers have often been bad at selling automation engineering jobs to the generation coming up. The single best way to do this is through co-op arrangements with schools, he says. How do you get them into engineering school in the first place? The single best way is to let them spend part of the time in school and part of the time in a real job. Companies and schools used to do a lot of that, and now they dont.

Miklovic sees the solution on a larger scale. Its not too late, but the problem of renewing our countrys engineering skills base has to be addressed at the highest level. Theres nothing you or I or Jeff Immelt [CEO of General Electric] can do. This is something that has to be done between the government and industry. Back in the 60s, the space race invigorated manufacturing. If something like that reinvigorated engineeringmaybe biofuels or renewable energythat would help.

Another editorial board member, Mark Wells, validation manager for generic pharmaceutical manufacturer Novopharm of Canada, disagrees. I dont think youre going to be able to spend your way into an economy and establish a dominant position. There are just going to be situations where overseas engineers will be practical. Im less concerned with not having available resources. Market forces will adjust to accommodate that.

Why Automation Engineering?

The outsourcing issue aside, the question remains, is automation engineering even worth pursuing as a career? Those we surveyed are divided on the subject. A full third think the gig was better 20 years ago, and another 14% are unsure, but that leaves 52% who dont think the good old days were better.

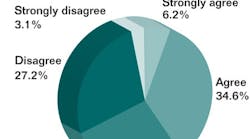

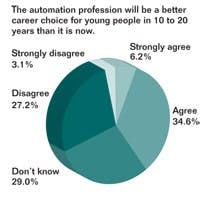

Pushing the question to the future leaves the answers even more unclear. Forty percent think process automation will be a better career choice in 20 years than now, but, again, almost a full third (30%) dont think it will be, and almost as many (29%) dont know.

Novopharms Wells comes down firmly on the side of the doubters. There will be fewer automation engineers who work for end users than there are today. Its not a growth career. Fewer and fewer people are needed to produce things, and that trend will continue.

The graying of the workforce may be skewing the results, says Georgia-Pacifics Larry Wells. As an older person, I know that Ill have work, he says. We talk about how we need people, but now we hire older ones. If we want a young person just out of school, thats no problem, but if we want an experienced person, theres a void in the middle, so we end up hiring the older person.

Better Times Ahead?

Forty percent of those surveyed say yes, but 30% disagree and another 30% are uncertain.

Miklovic is the most optimistic of our board members. The good news is that its not a dead-end career. There are going to be a lot of job opportunities, but theyre going to be in instrumentation, service and repair. My odds are better at getting a job at Anheuser-Busch managing beer-making controls than they are working for Fisher Controls designing new controls. A lot of that is going to be done in India.

A Different Kind of Engineer

The nature of the job is also subject to debate. Many see the basics remaining. Editorial board member Jim Sprague of Saudi Aramco said in an email, The basic function of a process control engineermeasuring and controlling the processwill be the same. The future will change the tools we use to do this, and will increase the number and type of people that look at the data, but understanding the chemical process and the physics of how to measure and control it will remain the bedrock skill set.

Dan Miklovic adds, Most automation people got there because they became process experts. They understood what they were making. For example, they had to learn how to make lumber and then how to automate the process. Being an automation engineer without understanding what youre making is hard.

But having said that, a whopping 84% of the readers we surveyed say the job of the automation engineer is going to be a different one in the future.

Convergence is the name of the game, says Miklovic. So many things are now in the realm of IT that control people need to think about what they should give up and what they should keep. If we dont break down the wall between control and IT, then were going to build up wasted investments. Control engineering should be focusing on the process and let IT worry about the computers. They already know how to do those things.

Novopharms Mark Wells says, The automation engineer is going to be taking on more responsibilities. [He or she] will have to know more technically, but will be more in charge of sourcing, purchasing and implementing through others rather than actually doing the work. Engineers will be more managers of resources coming from suppliers. Whatever application they encounter, theyre going to have to be able to source solutions, understand whats technically available, make the best choice and manage the implementation.

He goes on to say that soft skills such as project management, in addition to the traditional technical skills, will be increasingly important, and those technical skills will be less in depth and more broad-based. Theyve have to know a little bit about a lot of technologies, enough to make educated decisions.

The Sales Department

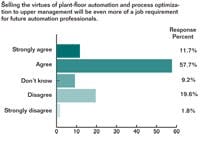

Nearly 70% of those surveyed see selling the benefits of plant-floor automation and optimization to the executive suite as a growing part of their job description in the future.

Being bilingual, both in terms of spoken and technical languages will be a necessary skill, says Miklovic. This isnt really new. The most successful companies have always been the ones where someone knew how to sell the business case for the technology. They had senior engineering people who could explain the benefits of adopting this type of control.

Whats changed, he says, is the level of sophistication. Twenty years ago, the average management person didnt have a strong technical background. Today they all understand technology to some degree. The dialog is ratcheting up a level, and the sophistication of the person youre talking to is better. Before you had to spend time on the technology. Now you have more time to spend on the business case.

Our survey reflects this focus on the larger business as well. Almost 79% of respondents say that future engineers will have to have business process analysis skills, and 70% think that selling process automation to upper management will be a bigger part of their job in 20 years than it is now.

What About the New Stuff?

The last question in our survey asked readers to rate which of five technologieswireless, nano-technology, alternative energy sources, increased computing speed and power and Internet-based monitoring and controlwould change the automation landscape the most. Wireless and Internet-based monitoring and control were in a statistical dead heat, at 43.2% and 42.6%, respectively.

Larry Wells says they will all matter to one degree or another. Each will change it in a different way. Wireless will make things cheaper. Well get more information at a lower cost. Nano-tech could change the whole world if it lives up to its advertisement, but its still very far in the future. Alternative energy will not change automation tech, but will create more job opportunities. The computer speed thing will change the landscape the least. We have Internet-based monitoring and control now. It will change the location of where we do some things, but wont change what we do. No one thing will supersede or preclude the others.

Keeping Away the Elephants?

Will the changing nature of the job cause automation engineers to morph into corporate drones, albeit ones with a better grasp of physics and chemistry than the average bear? Will the emphasis on soft skills and being generalists turn them into the English majors of technology−nice people, no doubt, but not really experts in anything? Should they just pack it in and get their MBAs instead?

The majority of those surveyed would answer a resounding, No! But the question is why.

Perhaps it has to do with Larry Wells elephant story. This is the one where the man pays a hunter with a big gun to keep the elephants away from his store. When it is pointed out to him that there are no elephants in the country outside the zoo, he says, See. Its working.

I use that story to explain why we spend money on automation engineers, says Wells. Why are we paying these people when the system is working on its own? Its working on its own because you had the people there. Its keeping away the elephants.

Novapharms Mark Wells has a slightly more romantic take on the profession. He says, I work with Nels Tyring, and he says, you dont go into this for the money, but because its a really interesting career. Monetary rewards are great, but you have to love your job. There are the intellectual rewards. You get some interaction with things that move and go. You get varied projects. Theres a great satisfaction in performing these jobs, and a great sense of accomplishment.

For the complete results of our survey, go to www.controlglobal.com/futuresurvey.html.

For a look at how women in the engineering workplace may change it see Work/Life Balance from our June.

Leaders relevant to this article: