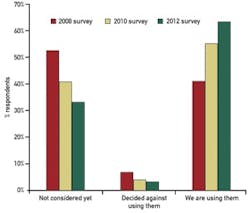

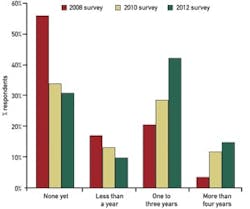

But that is finally changing. Earlier this year, Global Automation Research released the results of a survey of end users of wireless process instrumentation transmitters and found that 67% of those surveyed were using them, compared to 43% in 2008, an increase of 50% in just four years. Furthermore, wireless technology has moved from small test applications and simple monitoring to safety, asset protection and mainstream problem solving—and even some control. Furthermore, 63% of the respondents worked for companies that had considered using wireless, up a full 20 percentage points from 2008. The number of respondents working for companies that have decided against using wireless dropped to 4% (see Figure 1).

The benefits reported include savings on materials and labor, increased efficiency, increased data accuracy and easier maintenance. One of the respondents summed up the savings for his company this way: "[Wireless is a] very cost-effective method to bring additional points into the control system. We are seeing wireless installation costs about 70% less than a similar wired installation."

Joseph Citrano, global wireless product marketing manager for Honeywell Sensing and Control, says, "What we're seeing over the last year is that the early adopters have gone through the experiment and are implementing it [wireless] in a meaningful way. More people, who are followers, are just getting their feet wet. They're doing fewer applications, but there are quite a few folks doing more and more."

Remote Access

Getting necessary and, if not necessary, certainly useful data from remote areas of operation at a reasonable cost is a big driver for implementing wireless.

At specialty chemicals manufacturer Lubrizol's Deer Park, Texas, facility, wireless monitoring is in place in the tank farm. Keith Simpson, Lubrizol's I & E controls manager at Deer Park, explains: "The Deer Park tank farm is hundreds of tanks spread around the manufacturing facility, and some are across the road and in outlying areas. We're installing wireless transmitters for tank pressures and temperatures."

Cost was a big factor in making wireless an attractive option, and not only because the cost of running all those wires was eliminated. "People frequently forget that not only do you not have to pay for the wires, conduit, etc, but also, you don't have to do the engineering design. Wireless eliminates that cost as well," Simpson explains. "We had to decide where to put the wireless gateway and the switch, but that's what the engineering was restricted to."

Lubrizol went with the WirelessHART protocol for the same reason that many end users choose one protocol over another. "Most of our wired apps are HART," says Simpson.

Furthermore, Lubrizol uses Emerson's DeltaV automation system and its AMS asset management suite, both of which integrate seamlessly with the HART protocol. That AMS integration was another selling point for going wireless. "You can capture all that data and get it in AMS if you're using wireless," Simpson says.

Lundbeck Pharmaceuticals Italy, a producer of active pharmaceutical ingredients and cGMP intermediates in Padova (Padua), overcame its remote facilities problem in a similar fashion. The company needed to monitor and record groundwater levels at 10 monitoring wells around the facility.

According to Nicola Ribon, a project engineer at Lundbeck, the company began by monitoring three wells using a wired solution, but when the project expanded, and those wells on the periphery of the plant were included, wireless became the answer. "Because of the distances between those wells and the recorder, we chose a wireless solution. Moreover, a couple of wells are outside the grounds of the facility in the middle of the street, so it was impossible to reach them with cables."

Timing was another factor in the decision. "We needed to use the system for only a short period, probably a year," explains Ribon. "After that we can reuse the wireless system to collect and record other kinds of data. That's not possible with cables; you need to dismantle them."

The wireless technology is from Endress+Hauser and is based on the WirelessHART protocol. "Basically [we chose these products] because we just used Endress + Hauser level transmitters for the first cabled application. We know the performances of these transmitters, and we choose to maintain the some partnership with E+H also for wireless application," Ribon explains.

Oil and gas giant Petronas, based in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, is running a pilot project at its granular urea plant in Gurun, Kedah province. According to A. Aziz B. Ahmad, project engineer, "We are using wireless applications to monitor pressure and tank levels. We're using it to bring local information back to the control rooms."

As with many wireless converts, cabling plays a big role in the decision to cut the wires. "We run out of spare cable," Ahmad says simply. He adds that knowing that wireless technology was going to be used only for monitoring and not for control was also a factor in making the move. Although wireless for control is certainly a possibility in the future, for now, no one is ready to take that leap.

Ahmad says that his team had the choice of going with either the WirelessHART or the ISA 100.11a protocol, and they chose ISA 100, or more accurately, they chose technology from Yokogawa, which uses the ISA 100.11a protocol. The standards issue didn't really arise, says Ahmad. "Yokogawa was the first to offer their transmitter," he says.

The company also offered significant backup and support. "Yokogawa played a critical role in getting us comfortable with the standard and the wireless field technologies. They have conducted site surveys, given the appropriate support and even imparted valuable knowledge to our engineers during installation phase," says Ahmed.

So far, Petronas' experience has been a good one. In fact, says Ahmad, "We are satisfied with the progression and the proposed solution this far and are seeing smooth integration between Yokogawa's wireless products and our existing system. We will explore the expansion of wireless in our operation, as we are seeing very positive throughput with the wireless solution installed in our plant. In fact we have added another wireless installation for tank level measurement and upgraded our PRM system to enjoy more asset management benefits."

Other Uses

Wireless isn't just about remote connectivity. Another focus is on diagnostics. Over the last year or so, the MOL Plc Danube Refinery in Százhalombatta, Hungary, has been developing a strategy for expanding the use of wireless in its operations with a focus on two areas, monitoring and diagnostics, says Gábor Bereznai, head of instrumentation, control and electrical at the refinery.

Keeping an Eye on the Tank Farm

Figure 3. At Lubrizol's Deer Park, Texas, facility,

temperatures and pressures at the tank farm are

monitored wirelessly. Courtesy of Lubrizol

MOL will be monitoring corrosion, the temperature of fire heaters, the efficiency of heat exchangers, temperature and differential pressure transmitters and the open/closed position of valves.

The MOL refinery was the 2010 HART plant of the year, so it already has a strong infrastructure of wired HART devices, but there were some problems. Bereznai explains, "We had positioners we couldn't use because the gates between the positioners and the DCS were not HART-ready. Our explosion-proof barriers weren't HART-ready either."

So the company went to Emerson for THUM modules (The THUM can be retrofit on any existing two or four-wire HART device, enabling wireless transmission of measurement and diagnostics). The THUM adapter "allows us to get around this problem," says Bereznai.

The THUM adapter also allows MOL to connect many of its field devices to its Emerson AMS asset management system, and in another adaptation, meet government emissions reporting requirements. "We created an app where we can use pyrometers and THUM adaptors together to measure emission rates," says Bereznai.

And don't forget safety and security functions. Wireless monitoring of eyewash stations and safety showers, as well as personnel location, is an easier sell, perhaps, than applications such as monitoring and maintenance. Such applications are available from many vendors, including Honeywell, Emerson, Apprion and BS&B Industrial Wireless Solutions, among others.

Glitches

As effective as these solutions are, getting them running is not all roses and lollipops. As with any new technology, there are glitches in the system and a learning curve.Honeywell Sensing's Citrano observes, "Early on people had bad experiences with wireless because it wasn't really fit for the purpose. When you got into discussions with people [we found] reliability and security were issues. Battery life was a problem too, but as people get better at setting up their networks—they would have too much messaging going over one node—as they get more experience, they can avoid these problems."

Lundbeck's Ribon reports, "At the beginning we had some problems with communication between some repeaters/adapters; we discovered some radio noise due to a huge radio antenna place about 300 m from our facility. We solved the problem by moving some repeaters in areas where there was less interference and by placing some shields near the repeaters."Speaking about MOL's integration of field instrumentation with the refinery's AMS system, Bereznai says, "When we started, the communication was slow. We wanted to create a fingerprint curve, which is very communication intensive. Working with Emerson, we developed a fast-loop function to help with this, but it took some time to find the solution. Emerson in the U.S. helped us find the solution."

The reality is that at present, at least, most wireless users find the systems too slow to use for industrial control. "You can have problems with interference, and you can lose some data," says Ribon. "This is acceptable only for monitoring non-critical parameters."

He adds, "In any case, before you start an installation, you need to do an engineering phase to verify the feasibility, checking for interference."

On the other hand, wireless systems can be surprisingly reliable. "In the last two years, we've had bad storms with very heavy lightening and have had no problems [with the wireless]," says Bereznai. "We also did welding just a few centimeters from the transmitters, and that didn't affect the signals."

Bereznai adds that MOL hasn't replaced the batteries in his system in the two years it has been operating.

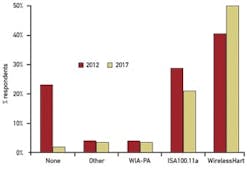

The Elephant in the Room

If there is one thing still making many potential wireless adopters uneasy, it is the on-going debate about on which protocol to standardize. According to the Global Automation 2012 survey, 40% of the respondents are waiting for a single international standard, up from 20% in 2010.

The politics of the matter aside, in many respects, they are equally valid and useful. There are differences between them, but they are not insurmountable. The choice the end user makes will depend on what his or her goal is.

Process Automation Hall of Fame member Tom Phinney, who has been instrumental in developing both WirelessHART and ISA 100.11a, says, "WirelessHART is more restrictive in terms of its development potential. ISA100.11a is built around the Internet and IPV 6, [the latest version of the Internet protocol]. In the longer term, ISA 100.11a has more potential. WirelessHART does not use standard Internet technologies, but those will be available to leverage with ISA 100. ISA 100 has great longevity built into it. The truth is, it will be a next-generation protocol."

But WirelessHART has its advantages too, says Phinney. "WirelessHART is easier to understand and implement than ISA 100. It has progressed further in terms of implementation and product variety."

One way to think about it is that from and end-user perspective, it's rather like deciding whether to get an iPhone or an Android phone. Both will do what you want them to do. But an iPhone has many more apps and is nearly plug-and-play. It also got out of the gate earlier and in a sense "owns" the marketplace. But it also is a closed environment. Android phones got out of the gate more slowly. They have a smaller app store. They don't have as "cool" a reputation. But their environment is a more open one and gives users more choices in terms of which systems (and phones) to use. But in either case, if your choice works for you, it's the correct one.

Practically speaking, "Some of the minutae are different, but functionally they are similar," says Mike Cushing, product marketing manager for pressure and temperature products at Siemens, which makes WirelessHART-compatible products. "ISA 100 is a larger umbrella for all kinds of communications. WirelessHART is more focused on instruments connecting to the control system. There are some technical differences, but they are not huge. ISA 100 is trying to cover all wireless applications in an operation, where WirelessHART is focused on instruments alone."

Wayne Manges, program manager at Oak Ridge National Labs, chairman of the ISA 100.11a standards committee, and a veteran wireless evangelist, says, "WirelessHART is simpler to deploy, but ISA 100 is more flexible."

He adds, "If you have a process or application that cannot stand more than 100-ms latency, you can't use WirelessHART. If you don't want to have to pick a lot of options, ISA 100 may not be what you want because it has options for better security, reliability and throughput. WirelessHART is meant to have no options. WirelessHART also has lower growth options. ISA can go up to 10,000 sensors. WirelessHART in that case would require intermediate networks and servers, etc. ISA is meant to be part of a whole suite of standards. If you want to do RFID, you have to use a separate system in WirelessHART."

Not everyone completely agrees with this assessment. Mark Nixon, research director at Emerson and a member of the Process Automation Hall of Fame, who has also been involved in the development of both Wireless HART and ISA 100.11a says, "Both WirelessHART and ISA100.11a provide mechanisms for allocating communication resources. In both cases, the user may decide to influence the number of hops between the device and the gateway by locating access points and backbone routers. In the case of WirelessHART, the standard allows for placing many access points. In the case of ISA100.11a, the standard allows for using multiple subnets. From the standpoint of latency, there is no technical basis to state that either WirelessHART or ISA100.11a is better."

He goes on to say, "The security specified by WirelessHART is very similar to ISA100.11a. The differences boil down to a couple of key things: ISA100.11a allows users to disable security and provides partial support for over-the-air provisioning (OTAP). I would argue that allowing security to be disabled creates more work for users—it forces users to have to check security settings. It also creates a security concern for users in that a) they may have missed enabling security, and b) it could open a vulnerability allowing hackers to disable key security settings."

He continues, "With WirelessHART the mesh is always on. ISA100.11a allows for the mesh features to not be enabled. Since mesh networks are inherently more reliable, for ISA100.11a to have the same reliability as WirelessHART, mesh capabilities must be enabled."

Nixon also argues that ultimately WirelessHART does have better throughput than ISA100.11a.

If you have wondered why the wireless standards war has been so long and protracted, now you know. The good news is that for those of us without a scorecard, there is a way through the technical maze.

Manges, one of whose briefs is to work with the Dept. of Energy and the Advanced Manufacturing Office to encourage the use of wireless and make it available for use with the smart grid, says, "In a way, you don't need to reach a standards agreement. It really doesn't matter who wins. The technology is there to work together. Protocols are designed to co-exist with others without hurting one another. WirelessHART and ISA are not interoperable, but they can co-exist."

And he offers a final word of advice. "If you're trying to decide which protocol to use, the worst answer is to do nothing. Use what you have. It's an enabler. The sooner you get into it, the sooner you can implement change."

Leaders relevant to this article: