Fieldbus Wars continue

LAST MONTH, at Hannover Fair in Germany, the press releases were flying: Profibus claimed to have 15.4 million nodes installed worldwide, with 530,000 in process systems. ODVA announced its 1 millionth EtherNet/IP node had been shipped. (Way back in 2003, Rockwell Automation announced that that it alone had shipped more than 1 million DeviceNet nodes.) Foundation fieldbus appears to be leading in process control applications, claiming 625,000 devices and 10,000 systems installed. Though some don’t call it a fieldbus, ARC Advisory Group estimates that some 10 million HART-enabled devices are in the field.

Complicating the matter is wireless. At Hannover Fair, 40 companies exhibited wireless automation devices. Clearly, a battle is shaping up. The next Fieldbus War, perhaps. And some end users are getting tired of it.

Can’t They Play Nice?

“I would put the fieldbus wars in the same vein as left-handed versus right-handed driving, English versus metric measurements, letter size versus A4 size, Beta versus VHS format and other contests,” says Eric Marcelo, senior instrument specialist at Nestle Phils, Cagayan de Oro Factory, in the Philippines. “A group of people came up with the fieldbus concept and developed it. Another group thought they could do better or maybe were unwilling to lose their own technology if they adopted the other group's system. Maybe it's just plain old human pride but the result is the same—chaos. “Instead of banding together, and coming up with a universal standard, developers continue to push their systems, hoping for the trigger that will one day eliminate all other contenders. In the meantime, we end users are caught in the crossfire.”

Patrick Rossi, process automation project manager at Mead Johnson in Evansville, Ind., adds, “The splintered state of fieldbus has left end users unable to decide which buses to embrace. With no clear choice to inexpensively deploy to address analog and discrete instrumentation and motors, our choice is not to choose. We'll just wait for the next ‘breakthrough’ technology to emerge to reduce initial and residual costs.”

Ken Smothers, I&C maintenance supervisor at Aquila Lake Road Station, puts it simply: “We considered it for one project, but we rejected it based on the known complications and the plant's lack of confidence in the technology.”

Ed, a refinery engineer, who must remain anonymous, adds, “Vendors generally don't like to play nice together. We recently installed 300 Foundation fieldbus instruments on a new refining unit in the U.S. We had plenty of problems getting devices to talk to our system. It did eventually happen, but getting the right device descriptor files wasn't easy.”

Still, Ed says he’s happy with fieldbus. “The installation is very clean. I've enjoyed some of the diagnostic capabilities and the ability to interact with the instruments from the control system. Being able to get the actual valve position back from the positioner solves a major control engineer headache—knowing whether or not the valve is working, and more importantly being able to get it fixed.”

On the other hand, some fieldbus users have no complaints. Air Products’ plant in Wichita, Kan., recently installed a Simatics PCS 7 control system with Profibus. “We’re pleased with the improvements and cost reductions from the Profibus installation,” says Dean Kerr, senior engineer at Air Products. “The project was completed on schedule and below budget. Profibus gives us the broadest choice of field devices from a large pool of name-brand suppliers. We can seamlessly integrate all of them on our network.”

Fieldbus Here to Stay

“I agree that the current state of fieldbus is in a tremendous state of flux, with technology moving way faster than customer acceptance,” says Arnold Offner, national/international committee manager for Phoenix Contact. “In North America, most of the latest fieldbus process installations have been upgrades to existing plants, with a resulting improvement in efficiencies. However, all the new fieldbus projects are in other parts of the world.”

The oil and gas industry was one of the first to embrace fieldbus technologies, and continues to be one of the primary fieldbus users. Brunei Shell Petroleum Co. installed Foundation fieldbus technology on this unmanned offshore platform. Source: Emerson Process Management

Kristen Barbour, product manager at Pepperl+Fuchs, says the oil and gas industry (See Figure 1) is a big driver. “Today almost all greenfield installations in the oil and gas industry are using Foundation fieldbus,” says Barbour. “Because the industry’s users were early proponents of Foundation fieldbus, they were early testers of the technology, and are very committed to it, not only for the installation savings, but also for the long-term cost savings that fieldbus provides.”

One of these savings involves maintenance costs. “A major oil company performed an internal study on conventional 4-20 mA installations and learned that approximately 60% of the times that maintenance personnel went into the field to check an instrument, the trip was unnecessary,” Barbour notes. “The return on investment can be measured in the short term from installation/commissioning savings, and continues through long-term savings resulting from proactive maintenance and fieldbus monitoring capabilities.”

Rockwell Automation agrees: “Over time, user adoption of ‘smart instruments’ (See Figure 2 below) in process applications will continue to increase as the tools required to configure, calibrate, monitor, and manage these devices also evolve,” says Dave Appleby, product marketing manager at Rockwell Automation. The company also believes that the value in smart instruments lies in the data they’re able to provide, rather than in the way users connect to them.

As you might expect, Siemens likewise sees increased Profibus sales. “Over the past five years, Siemens has seen a steady growth rate in our Profibus components sales,” says Moin Shaikh, Profibus marketing manager at Siemens. “A number of our customers are now employing Profibus in large process control applications and in mission-critical applications. Many of these customers tell us they’re seeing short payback times of their fieldbus installations.”

Meanwhile, Honeywell is riding the fence. “From Honeywell's vantage point, we’re seeing a significant upsurge in major process automation projects implementing fieldbus technology, specifically Foundation fieldbus, HART and Profibus DP,” says Tim Sweet, product marketing manager for Experion PKS at Honeywell Process Solutions. “Use of these technologies has soared in the past three years. Before that, people seemed to be experimenting. These technologies are now readily accepted and readily deployed. We think these fieldbus protocols are here to stay and are adding significant value to the adopters.”

Jane Lansing, PlantWeb marketing vice president for Emerson Process Management agrees: “When we first introduced fieldbus, almost all the fieldbus projects were ‘science projects.’ Users wanted to trial and test the robustness of the technology in non-critical applications,” she says. “This lasted a couple of years. Then we started seeing customers buy their second and third system, which were still small and non-critical. It wasn’t until 2001 that the first major, grassroots, fieldbus-specified project started up.

“Today, most major projects in the world specify Foundation fieldbus. Fieldbus is controlling mission-critical applications in all major industries, particularly in hydrocarbons. Emerson is seeing very strong double-digit growth in fieldbus. This has happened in just 10 years, which is a short adoption time in process control. The one thing that our industry surprises us vendors with, over and over again, is slow adoption.”

FIGURE 3: ETHERNET LUMBERS ALONG

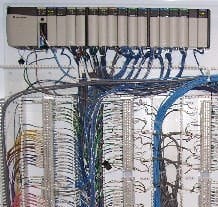

This control system for a planer/sorter at a lumber mill has an Ethernet-based fieldbus (blue wires) and A-B PLCs. Source: Concept Systems

Scott Saunders, sales and marketing vice president at Moore Industries, adds, “Interoperability between vendors has been and always will be a bit of an art. Many vendors implement versions of standard fieldbuses, but users often verify that just because a transmitter supports a fieldbus doesn’t mean it will just start communicating out of the box. Organizations like the Fieldbus Foundation, Profibus Trade Organization, and OPC Foundation will continue to play a key role in vendor compliance with fieldbus standards.”

Saunders also thinks fieldbus is here to stay. “Foundation fieldbus and Profibus still have their places on the plant-floor, where wireless is less popular,” he says. “While many users are implementing wireless technology, many seasoned process control engineers still prefer wires to wireless. Supervisory control and data acquisition are often accomplished by wireless networks, but critical control loops are still hardwired. This is where fieldbus technology offers peace of mind to the process control engineer.”

Charles Piper, fieldbus product manager for Invensys Process Systems, also believes in fieldbus’ staying power. “You can expect Foundation fieldbus, HART, Profibus, DeviceNet, and other fieldbuses to be with us for some time to come,” he says. “They meet today’s needs quite well, and gain considerable inertia from large investments made by vendors and end users alike. You’re more likely to see gradual physical layer evolution than significant change in the upper communication and user layer portions of the technology behind these standards.”

But Which Fieldbus?

When it comes to choosing a fieldbus for process control, the big five appear to be Profibus (See Figure 4), Ethernet, Foundation fieldbus, DeviceNet, and HART. Some people claim that HART isn’t a fieldbus, but we beg to differ. Though HART doesn’t have all the bells and whistles of the others, it can perform many of the same functions.

Sasol, a large chemical company in Sasolburg, South Africa, uses HART as a fieldbus. “We have excellent experience with HART technology, and have standardized on HART for our field devices,” says Johan Claassen, engineering manager at Sasol. At its plant in Midland, South Africa, Sasol has 3,500 HART instruments tied to a Honeywell PlantScape system. “We believe one of the improvement areas for HART is the speed of communication. Up to now this has not been problematic, but for larger installations this can become troublesome.”

Similarly, some may claim that DeviceNet is strictly for discrete automation, but Rockwell sees it as a critical part of a networking strategy for discrete and process control applications. “The networks we support share a common protocol enabling seamless flow of information between all components of Rockwell’s Integrated Architecture from the smallest device up through the enterprise business system,” explains McEldowney.

Likewise, others claim that Ethernet, by itself, isn’t a fieldbus. However, Ethernet is incorporated in several of the major fieldbuses in one form or another. “Ethernet is not threatening, but rather speeding up the installation and commissioning of Foundation fieldbus’ HSE, Profibus’ Profinet, DeviceNet’s EtherNet/IP, and some other fieldbuses,” notes Offner of Phoenix Contact.

Rockwell’s Appleby agrees, explaining, “It's important to remember the fieldbuses provide a standard for the data transmitted, while Ethernet provides a standard for transmitting the data. Networks define the physical link for moving the data, and fieldbuses define what the data is and means. Each technology brings something to the equation—it’s about the protocol and the data that's in the device.”

Some end users have used them all. For example, Dayton & Knight are consultants in North Vancouver, B.C., who work on water/wastewater systems, pump stations and treatment facilities. “We have used DeviceNet, Modbus, Profibus, and Ethernet on various projects,” says Doug Rhodes, manager of Dayton & Knight’s electrical power and automation group. “For example, we used DeviceNet to link drives and starters within treatment facilities. It’s robust, but a bit costly and tricky to set up. We used Modbus to link drives and starters within pump station MCCs. It’s less robust, but it’s economical and easy to set up. We used Profibus for instrumentation several years ago with no major issues, but would at least review Foundation fieldbus if a similar application arose today.”

Rossi, of Mead Johnson, reports that he’s used AS-interface and Profibus. “We've used AS-i, and as ‘easy’ as it is purported to be, we got bit by low-power dropouts on solenoids,” he says. “We’re using Profibus protocol to communicate with Mettler-Toledo scales, and have been happy with the results.”

Marcelo, of Nestle, doesn’t care which fieldbus he buys, as long as it works. “The feature that I want most is plug-and-play,” he laments. “When we first installed a fieldbus in our factory, the project engineer spent hours configuring and reconfiguring. Then, one day, a whole line of instruments stopped working. The engineer had to reenter the configurations one by one. The claim was that you'd only need to reload the configuration file, but that didn't work. Having experienced this, I'd want a system where I could get a pre-calibrated instrument, set its address, connect it to the fieldbus, and I'd be up and running. No need for setting up configurations or setting up communication parameters.”

Bradford, of Concept Systems, adds, “If the people designing instrumentation systems ever had to actually install and use them in a real plant, they might do things differently. People running plants aren’t interested in technology for technology’s sake. They view technology as nothing more than a tool, and need to know that the technology will help them achieve their goals without getting in the way of smooth, productive plant operation. In the absence of demonstrably better solutions, plant managers want to stick with what they know will work.

“Control system designers need to put themselves in their customers’ shoes, and analyze, from a plant’s perspective, whether a new piece of technology will add value. For example, if a fieldbus instrument designer was to follow the product from the factory to the customer’s plant and observe the calibration issues that the customer has, then the designer would do a better job of providing calibration support for future products. Factory calibration doesn’t always hold up, and things change at the installation site from when a system is initially specified. You need the capability of evaluating the instrument in the field and recalibrating it.”

Piper, of Invensys, says it really doesn’t matter which fieldbus you choose. “There are two essential functions of fieldbus,” he explains. “First, of course, is communication of measurement and actuator data for automatic, digital control of the plant, which provides significantly improved accuracy over conventional analog technologies. Second is the integration of digital instruments with the computer-based human interfaces that enable one-on-one interaction with these devices. The future of fieldbus isn’t so much in the physical media, or even the communication protocol, but in the functionality of new plant automation applications and their coupling to functionality within the field device. The physical layer is simply a means to that end.”

Based on what we’ve heard so far, it seems that HART, Profibus, Foundation fieldbus and DeviceNet are being used far and wide in the process industries with reasonably good success.

Not all instrumentation is fieldbus-compatible, however, and so vendors are feeling the pressure to convert their HART-based and other standard instrumentation to fieldbus. With many major, new projects going to fieldbus architectures, these vendors have to comply with fieldbus or lose the business. Moore Industries, for example, acquired a line of Foundation fieldbus and Profibus PA device couplers and power supplies from U.K.-based Hawke International, so it could expand its interface solutions for new and old projects alike. This allows Moore to offer fieldbus instrumentation along with fieldbus power supplies and device couplers for new Foundation fieldbus and Profibus projects.

Likewise, Softing recently announced a small Fieldbus Kit board that converts HART-based devices to Foundation fieldbus and Profibus PA. Fieldbus issues that remain unresolved are a universal, wireless, fielkdbus standard, the ongoing EDDL versus FDT debate, and fieldbus safety systems. As you might expect, the various standards committees are waffling, as major vendors try to force their particular technology into each standard. Still, progress is being made.

While they waffle, at least two 800-lb gorillas are lurking in the weeds, threatening to upset the fieldbus apple cart—Ethernet and wireless.

"Ethernet and Nothing Else"

That was the banner over a giant Automation IT booth at Hannover Fair, featuring exhibits from a host of companies, including Cisco, GE Fanuc, SAP, Pepperl+Fuchs, Harting, Sick, OSISoft, Fluke, and two dozen others, all linked together in an Ethernet network. Their premise was that Ethernet could link an entire enterprise, from IT to factory automation.

Although I didn’t see an example, booth literature claimed, “Line topologies such as the common fieldbus guarantee minimal effort and simple expandability.” That implies Automation IT is right outside the fieldbus door, and soon will be knocking to get in. Automation IT also claims it “provides direct, real-time access to all data in any application from any core process.” Knock, knock.

GE Fanuc, one of the Automation IT exhibitors, is a believer in Ethernet for fieldbus applications. “GE Fanuc sees DeviceNet fading and Profibus flattening out,” says Bill Black, GE Fanuc’s controllers product manager. “Ethernet has the highest potential for growth. We’re seeing more requirements to support multiple protocols such as Modbus TCP, EtherNet/IP and Profinet. The advantage of Ethernet is the relatively low cost of installation versus the high cost of specialty connectors and cables for Profibus and DeviceNet.”

Black adds instruments with an Ethernet interface can serve the same function as a fieldbus. “There isn't anything a fieldbus can do that Ethernet can't, so there isn't a good case why Ethernet can't be used,” he notes. “There are many advantages of Ethernet, such as openness, cost of installation, and hardware cost.”

Rockwell’s Appleby agrees: “The value of open standards like Ethernet is that they give people a common format to work from. The trick can be determining which standards are truly open.”

Meanwhile, Moin Shaikh of Siemens disagrees: “The biggest difference between fieldbus and Ethernet is that fieldbuses are deterministic and standard Ethernet is not,” he explains. “Certain Ethernet protocol changes must be made to achieve deterministic behavior.”

According to Lee Neitzell, an engineer with Emerson, while Foundation fieldbus is bus-powered, and can be used in intrinsic safety applications, Ethernet can’t claim these capabilities. “First, it’s not intrinsically safe. Second, even in non-intrinsically safe applications, Ethernet as used today is no longer a bus. That means there has to be a hierarchy of active switches and each device has to have a separate, Ethernet cable run to it from its switch. This results in significant installation and maintenance costs, as well as reliability costs. Third, Ethernet isn’t bus powered,” he says. “Therefore, each device also has to have power run to it, resulting in even higher installation and maintenance costs.”

Barbour of Pepperl+Fuchs says Ethernet with a fieldbus protocol may be the answer. “To date there’s no power on Ethernet,” Barbour says. “Developers trying to realize an Ethernet fieldbus solution will make Foundation fieldbus technology part of the TCP/IP Protocol Stack. Ethernet will be a welcome addition to Foundation fieldbus to increase bandwidth and network speed. There are 10-12 Ethernet-based instruments on the market today that were built on the FF protocol.”

Skip Hansen, I/O systems product manager at Beckhoff Automation, says it’s only a matter of time before the Ethernet juggernaut takes over. “Industrial Ethernet continues to rise to dominance, starting with the open Modbus TCP/IP protocol, and progressing to the latest technologies with the advent of next-generation Ethernet fieldbuses such as EtherCat,” he says. “These protocols reduce equipment costs and reduce installation time by using commercial, off-the-shelf (COTS) components and cabling. Ethernet solutions differ from each other in performance: Modbus TCP reaches the ‘tens of milliseconds’ control level, EtherNet/IP delivers millisecond level control, and EtherCat (See Figure 5 below) gets down to microsecond level control. Other future Ethernet-based solutions available or under development include Profinet, Ethernet Powerlink, SERCOS III and SynqNet. Devices with Ethernet interfaces can and most certainly do handle the same functions as devices with proprietary fieldbus interfaces.”

Ethernet is getting faster and faster. This PC (left) and Ethernet switch (right) provide microsecond response time. Source: Beckhoff

What about Wireless?

Wireless is coming on the scene faster than a souped-up Corvette. As noted above, 40 vendors exhibited wireless automation products at Hannover Fair.

“Almost all industrial instrument and process control vendors have adopted some form of wireless technology,” says Saunders, of Moore. “Whether it’s 802.11 or some proprietary version boasting better security and throughput, the fact remains that wireless networks will continue to gain momentum throughout the process control sector. Ethernet and wireless Ethernet have become the de facto industrial wiring standard for both process control backbones and factory automation networks. Its ability to handle higher throughput, multiple protocols, low-cost of implementation and multiple vendor support will further allow Ethernet to displace many of the proprietary control networks that once dominated our industry. There’s no doubt that wireless Ethernet will continue its aggressive growth curve within our industry.”

But will it replace fieldbuses? Not in our lifetimes, says Emerson’s Lansing. “Wireless is a complementary technology to HART and fieldbus, and represents just the physical layer of the communications stack,” she explains. “It’s another ‘pipe’ to move the bits. Wireless Ethernet is actually also complementary, representing the physical and data-link layers. We have to remember that we still need a standard application layer on top of Ethernet, wired or wireless. That’s why almost all communications protocols offer an Ethernet version, such as Foundation fieldbus HSE, Modbus TCP/IP, Ethernet/IP, and Profinet.”

We have reservations, too. Wireless is a fine way to monitor data and transmit setpoint information, but it may not be suitable for real-time control when response is critical. Too many variables can upset the timing of wireless transmissions, including other wireless traffic, interference, electrical noise, and so on. We have no doubt that these problems will be solved some day, and wireless Ethernet will prove to be a dominant force in fieldbus.

It also seems that industrial vendors ought to look at consumer products as a guide to the future. After all, nearly every electronic consumer product from cell phones to microwave ovens has an embedded computer. For just a few dollars, it’s possible to embed a processor and a Windows CE operating system into every fieldbus device, router, and interface. Such a system would allow any process instrument to support Foundation fieldbus, Profibus, DeviceNet, HART, EtherNet/IP and wireless interfaces, all at the same time, if necessary. It could hold all the protocol stacks, device description (DD) files, EDDL files, FDT files and configuration files that anyone could possibly need.

With such a system, end users would not have to worry about vendors “playing nice” with each other, and they would not have to worry about which fieldbus to buy. The squabbles would be over, and we could all get back to doing process control.