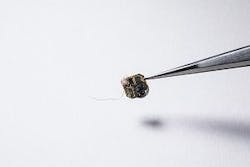

Computer scientists and engineers at the University of Washington have created a sensor package that is small enough to ride aboard a bumblebee. Source: Mark Stone/University of Washington

After we spent more than $100 on a drone for my oldest nephew, I was shocked that he only gets a few short minutes of play on every charge─doesn’t seem very fun to me. This frustration doesn’t only apply to commercial toys, but drones used to survey farms and other large areas of land also face this power challenge. In search of a way to solve this problem for farming and other large-scale applications, engineers at the University of Washington looked to nature for a solution.The engineers recently released the findings of their research, in which they developed a 102-milligram sensor backpack, which fits onto the backs of bumblebees, according to a recent article by Sarah McQuate in UW News titled “Researchers create first sensor package that can ride aboard bees.”

“Drones can fly for maybe 10 or 20 minutes before they need to charge again, whereas our bees can collect data for hours,” said senior author Shyam Gollakota, an associate professor in the UW’s Paul G. Allen School of Computer Science & Engineering, in the article. “We showed for the first time that it’s possible to actually do all this computation and sensing using insects in lieu of drones.”

Co-author Vikran Iyer, a doctoral student in the UW Department of Electrical & Computer Engineering, added: “We decided to use bumblebees because they’re large enough to carry a tiny battery that can power our system, and they return to a hive every night where we could wirelessly recharge the batteries. For this research, we followed the best methods for care and handling of these creatures.”

Because bees solve the problem of powering flight, this left the researchers to figure out how to collect the necessary data that the drone would have collected. The sensing system that the researchers developed is small enough to fit onto the back of a bumblebee and runs on a tiny rechargeable battery, which can last for as many as seven hours of flight and charges wirelessly while the bees are in their hive at night, the article reports.

The University of Washington team designed a sensor "backpack" that weighs 102 milligrams. Source: Mark Stone/University of Washington

However, development came with some challenges. The sensor backpack had to be small enough that a bee could carry it, and it must also be able to sense a bee’s location.Co-author and doctoral student in the Allen School explained in the article that the battery that powers the 102-milligram sensor backpack weighs 70 milligrams alone. Because of this, GPS receivers were out of the question, as they require too much power and would need a larger battery pack. To avoid requiring more power, the researchers developed a location tracking system using multiple antennas that broadcast signals from a base station. The sensor backpacks contain a receiver, which can triangulate the insect’s position, the article reports.

“To test the localization system, we did an experiment on a soccer field. We set up our base station with four antennas on one side of the field, and then we had a bee with a backpack flying around in a jar that we moved away from the antennas. We were able to detect the bee’s positioning as long as it was within 80 meters, about three-quarters the length of a football field, of the antennas,” co-author Anran Wang, a doctoral student in the Allen School, said in the article.

The backpack system is equipped with several small sensors, monitoring temperature, humidity and light intensity, which is all collected along with the bee’s location information. When the bees return to their hive, the backpack can upload the collected data via the backscatter method.

The backpacks can only store about 30 kilobytes of data right now, so only sensors that create a small amount of data can be used.

The research team will be presenting its findings at the ACM MobiCom 2019 conference.

About the Author

Amanda Del Buono

Amanda Del Buono

Leaders relevant to this article: