Zigbee, A Potentially Great Way to Save Energy

If you're running a refinery or chemical plant, of course, these savings must be balanced against costs, as much as $20-$25 per linear ft. to run wires so sensors can monitor leaks to $3 per ft. and make close monitoring practical. It’s called Zigbee.

| "What distinguishes Zigbee is that devices can set up their own mesh network, it can handle periodic or intermittent data, and most importantly it runs on very low power." |

In applications where precise temperature control is necessary (and that’s true for most basic production), wireless sensors can lead to fine adjustments that lower costs and increase yields.

Standards, of course, mean nothing without applications. Ember Corp. of

Honeywell has been working on a $10 million contract since early this year that aims to save $1 billion in energy costs (15% of the total), using Ember’s Zigbee technology. It’s the largest of several projects in a $115 million U.S. Department of Energy effort created by Congress aimed at cutting costs in eight energy-intensive industries.

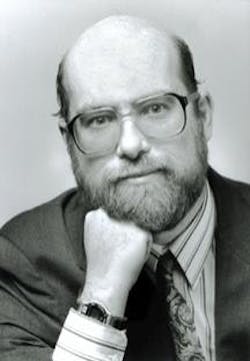

Dan Sheflin is Vice President and Chief Technology Officer for the Honeywell Automation and Control Solutions (ACS) business group. He sees Zigbee as a dynamite follow-on to his XYR wireless transmitter technology, which won Frost & Sullivan’s New Product of the Year award in the sensor category. "We have a line of pressure flow, and temperature level sensors that are XYR enabled," he said. But Zigbee enables a mesh network approach to this," says Sheflin. "The neat thing about mesh-topology-based networks is it will work around obstructions. Our customers don’t want to have to do a site survey to put in a system. They want to put sensors where they want to put them, an have it self-configure. That’s what we’re trying to work on. It will likely be built on Zigbee."

Tests will start this year at Alcoa, Dow Chemical, and ExxonMobil to track energy losses from piping systems and monitor the use of gases like ethylene in plastic plants. The network of Zigbee sensors, each the size of an old Matchbox car box, will monitor the gas constantly, letting managers eliminate leaks immediately.

Sheflin is also responsible for residential and commercial markets, and says "We see Zigbee potentially impacting all our spaces; from building controls and thermostats to security systems and fire systems."

The only problem, and it’s a short term problem, lies in standardizing the upper application layers of the Zigbee standard, but Sheflin expects that to be complete late this year. "Once that’s done we can build applications. Our industrial customers demand open standards. We’re not looking for proprietary advantage."

Following this year’s tests, Sheflin hopes to have pilot projects in place early in 2005, with actual products released by next summer. The "amazing" customer acceptance of XYR, which requires site surveys before installation, and line-of-sight use of the 900-MHz unlicensed band, tells Sheflin the market will be there.

Don’t worry about Zigbee, he adds, if you’ve already seen XYR. "We always focus on migration of our customers. Those who have XYR we’ll make sure we can upgrade them to the next standard."

Sheflin is already looking at how Zigbee might go into a major facility. He figures a central node, with regular power, could service 50 wireless sensors running on batteries.

"What’s great about Zigbee is its very low power consumption," notes Sheflin. "We’re talking about several years [of battery life], and our goal is [to achieve] more than that." There are very efficient power management aspects to Zigbee and those help Honeywell’s strategies for using these devices to minimize power consumption he says. "What you want in a system like this is for every sensor to degrade equally, so when you’re done, every sensor has consumed all its batteries. Zigbee won’t just save energy, he adds, but will have a dramatic increase on worker productivity in these plants.

Dana Blankenhorn, Business Analyst