By Jim Montague, executive editor

Being flooded with unusable data isn’t as bad as being flooded with bituminous oil, water, sand, steam or a combination of all four. But it’s not that much better.

Cliff Pederson, production processes manager at Suncor Energy Services in Calgary, Alberta, says this information tide began to rise at Suncor’s in situ water treatment, hot water and steam generation plant shortly after the company installed its first fieldbus system in 2001. The plant’s hundreds of smart transmitters, smart valve positioners and other intelligent devices began churning out mounds of diagnostic data and delivered it through Foundation fieldbus devices to Emerson Process Management’s Delta V software .

However, this information was still more than Suncor’s operators could initially digest or use to make preventive maintenance decisions. As a result, Pederson says they began seeking ways to screen their data and get it into a more usable form, and they started an asset optimization project two years ago. Suncor and its local Emerson distributor and systems integrator, Spartan Controls, implemented Emerson’s Delta V, Asset Management System (AMS) and Device Manager software to prioritize transmitter diagnostics and other messages in four to six criticality rankings, based on Suncor’s own risk matrix.

North of Fort McMurray, Alberta, Suncor drills pairs of horizontal wells in 1,000-ft deep Athabasca oil sands and uses steam-assisted, gravity-drainage to extract oil in a six-to-12-month period. The first two stages of Suncor’s facility have been built and now produce 45,000 barrels per day of bitumen. Stage 3 is under construction, and Stages 4-6 are scheduled.

“The most critical data is from safety equipment or devices that could create a safety or production incident if they fail,” says Pederson. “To determine these levels, our team defined and set its priorities in Delta V’s Asset Portal software, which then ranks incoming messages and displays them to engineers, maintenance staff and operators. Next, users initiate work orders and send technicians to fix problems. This solution is less reactive, allows more preventive fixes and enables more condition-based maintenance and operations.”

And they all lived happily ever after—at least until the next unresolved snag came up. But more on that later.

Refocusing a Fuzzy Map

Asset management has come a long way from the old days of reactive maintenance and running to failure—though many users continue to operate at this early stage. As it’s moved into use-based, scheduled and preventive mai ntenance and onward into condition-based maintenance, the asset management umbrella has grown to cover a dizzying array of topics and technologies. These include maintenance, operations, life cycle, data collection and processing, networking and enterprise systems.

“Process controls have always been focused on three things: monitoring and controlling their process, products and work environment. Now, they’re joined by a fourth piece, controlling equipment assets, which was previously a maintenance responsibility,” says David Berger, PE, partner at Western Management Consultants in Toronto. “And the condition-based monitoring and predictive maintenance that were always there to some degree become much more important, and use software to help monitoring conditions.” (See Asset Management Assessment sidebar.)

Existing Management Methods

For example, a two-engineer staff at Chevron’s plant in Sweeny, Texas, is using ExperTune’s PlantTriage software to monitor 70 performance parameters in about 2,000 loops. The software pulls data from the plant’s distributed control system (DCS) or its historian using an OPC connection, which can show more performance data than the DCS alone.

“Traditionally, technicians used to do rounds, but there aren’t enough people now, so PCs and software are needed to point them in the right direction,” says George Buckbee, ExperTune’s marketing manager. “PlantTriage also did a lot of the number crunching needed to help improve the moisture level in Sweeny’s products and stabilize its overall process. Doing this incorrectly could have costs the plant $10,000 per day.”

Likewise, fertilizer manufacturer CF Industries recently used Invensys Avantis Pro and DSS software to update the structured maintenance program at its plant in Donaldsonville, La. This program collects MRO inventory, procurement and maintenance activities. The new system automates maintenance planning and tracking of 50,000 assets and 60,000 inventory items, including vessels, pumps, rotating equipment and motors. “Avantis DSS takes data from available Microsoft documents, such as Excel, and makes useful information out of it,” says Dave Wiedenfeld, CF’s IT group project. “Data analysis that used to take two weeks can now be done in 10 minutes.” He adds that improved asset management allowed CF to reduce its inventory by several million dollars and saved it about $2 million via improved sourcing and contract negotiations.

“It’s important to understand that every asset has a state that it’s in, but now intelligent devices and their software can give us much more information about them,” says Neil Cooper, general manager of Invensys Process Systems’ manufacturing and business operations management division. “For instance, an intelligent valve can show that it’s 30% open, conduct an automatic partial stroke test or indicate pressures on either side of it. These new data sets can include up to 60 variables, and available condition-management software can aggregate it all, so users can look at whole process control loops, not just individual I/O points. Then, they can put context on this data and find problems that wouldn’t be visible otherwise. For example, they now can apply aggregate rule sets to real-time data and see the set of events that indicate a pump is likely to go bad because these events happened eight or 12 hours before the last one failed. Previously, users did an analysis and set a policy after a failure, but now they can get trends and plan ahead of time.”

OPC UA Aids Assets

“Previously, there was almost too much manual labor required to do asset management effectively, but users are leveraging standards, such as Mimosa’s XML schemas for devices, and aggressively undertaking custom-development projects,” says Tom Burke, OPC Foundation’s president and executive director. “However, writing custom software isn’t the best use of an owner/operator’s time, so they’re asking suppliers to do it and give them standardized devices. Suppliers are increasingly interested in adhering to Mimosa and ISA-95 with OPC as the transport because it allows them to optimize during production and calibrate beforehand and during design time.

“OPC’s transport services allow users to plug devices into an asset management system, so the system can pick everything up via read, write and subscribe functions. For example, an asset management system can use OPC Unified Architecture (UA) and its web services and standardized XML transactions as its interface for subscribing to plant devices. So instead of getting delayed data from clipboards or the DCS at the end of an eight-hour shift, users can now get information within minutes and make better maintenance and condition-based monitoring decisions much closer to real time. This means users don’t need to base a calibration decision, for example, on an arbitrary schedule that may not reflect reality closely enough. Now, they can make more dynamic adjustments, and compensate for changes in materials and change recipes as needed.”

Open O&M Bridge Opening

Back in northern Alberta, the snag that arose at Suncor was a persistent time lag after work orders were generated. Pederson says this headache occurred, in part, because Suncor also implemented SAP’s Plant Maintenance enterprise resource planning (ERP) software in January 2006, and the maintenance planning staff uses it to schedule maintenance tasks. “This creates a time lag between people because our Asset Portal and SAP systems aren’t connected,” explains Pederson. “So, when Asset Portal flags a problem, the maintenance planner using SAP doesn’t know about it. We needed to connect these two systems, but there wasn’t a way to do it—until recently.”

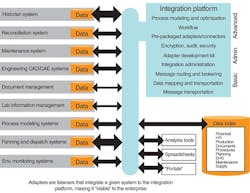

Figure 1: Open O&M will facilitate Suncor’s network’s transport layer and use “adapters” or “listeners” that integrate a given system to the integration platform, making it “visible” to the enterprise.

Courtesy of Emerson Process Management

Over the past several years, experts in various standards, including Mimosa, OPC Foundation, ISA-95 committee, World Batch Forum and the Open Applications Group have collaborated on a joint Open Operations and Maintenance (O&M) initiative to allow different asset management methods to coexist and be compatible.

Because users at Suncor don’t want to use direct interface or data warehousing for their data exchanges anymore, Pederson explains that Open O&M will facilitate the network’s transport layer and use “adapters” or “listeners” that integrate a given system to the integration platform, making it “visible” to the enterprise (Figure 1). “The aim is to make application-to-application interconnectivity and communication invisible.”

However, though this Open O&M architecture is complete, and Pederson says it will work eventually, it hasn’t been installed at Suncor’s plant yet. Unfortunately, this means his colleagues still are performing many asset management tasks manually. One of the few upsides is that all this manual work shows how much time, labor and money can be saved by using Open O&M.

Smoothing Human Roadblocks

Ironically, though asset management solutions are growing increasingly sophisticated, developers and users agree they won’t do any good if they don’t become part of routine, plant-floor operations. “The main obstacle to asset management is still people’s resistance to making needed changes,” says Berger. “Senior management needs to understand this and devote the resources needed to make these changes happen.”

Though its Open O&M solution is expected to be implemented at Suncor soon, Pederson acknowledges that the wait and various transitions have been frustrating, and that personnel issues still need to be addressed, too.

“We still need to engage our IT organization because their main focus has just been getting the enterprise to work, and so there’s still a lack of understanding between IT and manufacturing,” adds Pederson. “We need to get people talking to each other to increase understanding on both sides of manufacturing and IT equation. The technology part of asset management is easy compared to the people part. Many individuals used to be driving in different directions, and so the left hand didn’t know what the right hands was doing.”

Asset Management Assessment

David Berger, PE, partner at Western Management Consultants in Toronto, explains that the three basic types of asset management are run to failure, use-based by metering or schedule, and condition-based by using data from the device itself and previous trend data from comparable components.

To decide which strategy to use for a device, users must answer three questions about it: what does it do? what happens if it fails? and, what’s the best policy to have as a result?

Asking what happens if a device fails allows users to evaluate a range of safety, cost and environmental consequences from negligible to catastrophic. If a disaster is a possible result, then almost any cost of mitigation is worthwhile. If the consequence is negligible, then running to failure is acceptable.

Consequently, it’s important to conduct a cost-benefit analysis of possible consequences before selecting which asset management policy to use for each device. This means seeking the right correlation between each device’s operating variables and possible failure predictors, such as vibration and heat for rotating equipment or pressure and corrosion in a pipe. Next, users should decide on upper and lower control limits to help detect imminent failures and identify trend lines. So, if a device goes over a limit, then action can be taken, or if a trend line begins to fluctuate or creep towards its limit, then the device can be repaired or replaced.

Latest from Asset Management

Leaders relevant to this article: