Safety Requires Process Control Know-How

One of the lessons of the shuttle disaster should be to increase the role of the process control engineer in design. Whether it is the control of the landing of a space vehicle or the control of any other critical process, an essential prerequisite of safety is the full understanding of the process. The person who understands both the hardware and the software components of the controlled process must be the process control engineer.

Referring back to the shuttle disaster: When control algorithms are configured, it is essential their live zero can be distinguished from a loss of measurement signal. All process control engineers know this, but not too many others do. I am not saying there were no process control people on the shuttles design team or that the loss of measurement signals contributed to the tragedy. My sole purpose is to illustrate a possible chain of events, if some temperature sensors also served as measurement inputs of control algorithms.

If that was the case, when these measurement signals were severed, the loop could have interpreted the loss of input as a reading of low temperature and, in response, could have stopped cooling the aluminum wall. If a process control engineer was part of the design team, I am sure the wall cooling control algorithms would have distinguished a live zero from a loss of signal¦

Naturally, if there was no means of cooling the wall at all, that is even worse. All system components that can overheat in an emergency should always be protected by emergency cooling.

We learned from the accident at Three Mile Island that a high cooling water level signal does not necessarily mean that full cooling is being provided for the reactor. The level of cooling water can also rise because the water is boiling.

One would think such a simple point would be understood by now throughout the nuclear power industry and the required corrections would have been made. Yet, last year, when I reviewed the level measurement practices at a nuclear power plant, I found over a dozen such misapplications. In these level loops, only hydrostatic head is measured. Therefore, when the water is boiling, we know neither the level nor the mass of coolant inside the reactor or other tank.

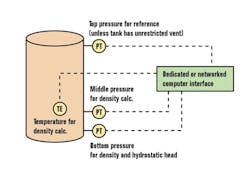

One solution to this problem is illustrated in Figure 1, where the use of multiple differential pressure cells makes it possible to independently determine density and total hydrostatic head. If, in addition, one also needs to know the interface between the boiling water and the steam, the installation of a separate refraction-type level detector is recommended.

On another consulting job, I was asked to look at the pressure relief valves (PRV) in an industrial plant. When I visited the front office and mentioned terms like overpressure, blow-down, pop-action, inlet drop, or back-pressure (superimposed and built-up), I got only blank stares. When I asked for the plants process control engineer, it turned out they had none. In this plant, management depended solely on the suppliers advice when it came to selecting PRVs.

One would have thought that by the 21st century all plant managers would know that no vendor can possibly understand the intricate personalities of their processes. When it comes to safety, they must not depend on the guesses of outsiders. Well, I was wrong. In this plant, they did not even have calculations on how much back pressure develops in their vent header when some PRVs are blowing and did not even know that bellows seals can protect the setpoints of their PRV from being shifted by back pressure.

Similarly, when it came to the discussion of PRV discharge capacities, they did not realize the full capacity of the valve is reached only when the valve lift is 100%, and it can take anywhere from 3 to 20% overpressure to get there. Similarly, they did not know that pilot-operated PRVs:

- Reduce leakage and simmering, because as the pressure rises, the forces keeping them closed increase;

- Have a capacity 20% to 50% greater than that of their spring-loaded counterparts; and

- Can withstand operating normal pressure of the process rising to 98% of PRV setpoint, because of their small blow-down, while it must stay under 90% for conventional ones.

In short, both the productivity of our industries and their safety requires the in-house presence of process control engineers. But top management does not yet understand that need.

Bla Liptk, PE, process control consultant, is also editor of the Instrument Engineers' Handbook and is seeking new co-authors for the forthcoming new edition of that multi-volume work. He can be reached at [email protected].