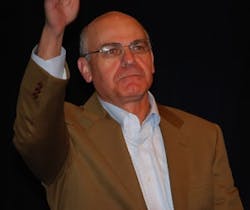

Emerson's John Berra Says Farewell

Tomorrow marks the end of an era at Emerson Process Management as John Berra, chairman and long-time leader, retires after 41 years in the process automation industry. Coincidentally, Sept. 30 also marks the date Emerson has chosen to retire number 1151, the jersey worn for 41 years by perhaps the most well known field instrument in automation history, the Rosemount 1151 pressure transmitter.

Both Berra and the 1151 exit the stage after remarkably successful runs.

"In 1969," Berra recalls, "when I started as an instrument engineer at Monsanto, we were using pneumatic instruments, and in the control room we'd have the occasional daring graphic painted on the wall with lights and things like that indicating status."

Berra's career spans the movement from pneumatic instrumentation to wired analog, to digital control, to fieldbus and now to wireless control. "Most of my career," Berra says, "has been about getting rid of wires. We tried reducing some of the wiring with fieldbus, and now, of course, wireless is fieldbus without wires. Anything we can do to reduce the complexity of wiring is added value to our customers."

Berra refers to automation as a noble profession. "I think the people who do this work are underappreciated. It was true back then, and it is still true today," he says. "Part of what I've tried to do is to create and increase the awareness that this profession is extremely important to the process industries."

Further making his point, Berra notes, "You can tally up the hundreds of millions of dollars that are spent on some of the largest projects in the world, and the automation piece is usually about 5%, maybe on the upside 10% of the total cost of the project. And one thing is for sure: If that 10% doesn't work, the rest of the 90% doesn't work either. So the responsibility of the automation engineer to make that plant run really well is front and center."

The most important trend over the past 40 years has been the movement to put digital technology into everything that does process control, according to Berra. "When I first began, a transmitter was an all-analog device with all-analog circuitry, and it did one thing: It made a measurement and it pumped that measurement out as an analog value," he says. "Today, the list of things that one of these instruments can do—just the horsepower that is in there—to do not only the measurement but the diagnostics, offers tremendous benefits. But the digitization of the control room side has changed the way we operate plants."

When the distributed control system (DCS) first came out—putting a microprocessor into a control system and sitting an operator in front of a screen—it was radical thinking, Berra says. "There was so much mistrust of this technology that many customers built full analog panel wall control systems, just in case the digital stuff didn't work," he says. "So I think the move toward ASICs and smaller, smarter chips has opened the door to all the advances in automation technology. That digitization is probably the greatest trend of the past several decades."

The current major technology trend is toward wireless, Berra notes, and the early benefit is the same as it was for fieldbus: the reduction of installation cost by reducing or eliminating wiring. "But what really happened is that the technology opened the doors to making better devices, more intelligent devices, and more clever and creative ways to accomplish process control," he says. "More importantly, it opens up whole new ways to visualize process control—not thinking about four sensors in a catalyst bed and trying to make interpretations about what's going on in the rest of the thing. But if you put lots of sensors there, these devices can tell you a lot more about what's going on."

Improving the number of sensors, diagnostics and preventive maintenance can reduce unplanned shutdown, thereby increasing profits, Berra adds. "Every customer I've ever talked to lists as his No. 1 cost issue unplanned shutdown—things that go bump in the night."

According to Berra, most universities don't prepare their student for working in process. "The space program doesn't have the drive it used to, and doesn't create interest in process control," he says. "It starts with university education, and the training that could be had…there should be more things like ISA's Certified Automation Professional (CAP) program."

There also needs to be more management education about automation's importance, Berra adds. "A lot of the managers—refinery managers and up—that I talk to really don't have an appreciation for what is going on in that control room," he says, noting that one problem is that when the plant is running properly, the automation engineers go unnoticed. "They say, 'I just don't want to hear from the control system. As long as I don't hear anything, I am happy.' The attitude is that all these control projects are zero ROI—you put new stuff in and nothing changes. And that is just so wrong! If we can educate management about just how important automation is, it will create the desire to go into the field and a career path for them."