Dos and don'ts of control room design

Among engineers, “design process” is a well-understood term. It may have slightly different elements across the various disciplines, but generally, it’s a methodical series of steps in which the mathematics and engineering sciences are applied in an iterative manner to optimally meet a stated objective. The architecture and design of a control building follows engineering design process principles. When it doesn’t, companies often end up with costly issues and high-risk decisions to make.

Over the past 25 years, our experience has provided a front-row seat as hundreds of leading oil & gas, chemical, utility, mining and transportation companies embarked on a new or renovated control room. Most often, these companies understand and appreciate good design process principles when it comes to designing new control buildings. But recently, compressed budgets and schedules, lacks of proper resources and project management, and poor end-to-end planning are causing companies to take shortcuts in the engineering design process that are difficult to rectify.

These shortcuts impact organizations in various and often costly ways. Examples include:

- A control room that has no room for future expansion of people or equipment.

- Control rooms with poor lighting, leading to employee complaints and higher rates of absenteeism.

- Noisy, congested control rooms with sub-optimal workflow adjacencies.

- Delays in design and construction schedules required to address changes.

- Control room designs that don’t meet ISO standards.

Imagine having to ask for additional funding to “fix” a new control building in which your company initially invested millions of dollars. When it comes to designing a new or renovated control building, taking shortcuts and potentially repeating missteps that others have made can be very costly. Missteps can be avoided by simply following good engineering design process principles. In this article, we will share examples of shortcuts and missteps we have observed, and offer tested ways to avoid them.

Begin at the beginning

In an ideal world, clients would invite their control-building architect to the table in the planning stages of a new operations facility or a control room renovation, long before the building location or size is determined and the consoles selected. An experienced control-building architect and designer can provide a clear process to identify predesign activities that will prepare companies to ask the right questions early in the process. Auditing existing facilities to understand current strengths and weaknesses, and to prioritize the most critical aspects of the project, is a step that, when skipped, can have a detrimental impact on the vision of the new control facility.

A control-building architect should have a well-defined process that starts at the beginning (predesign) and ends with support through construction, including commissioning. What follows is a synopsis of best practices in the control building design process.

Design for the user

The term “operator-centric” is ubiquitous in the process industry. Best practices in engineering design for mission-critical, 24/7 control buildings is to design from the operator outward. This is more than just asking operations what’s required for a safe and productive control room. A thorough understanding of how the operation works in all modes is necessary: steady state, shift changeover, upsets, startups and shutdowns. What is the expectation and process for operating the plant in each of these modes? A good engineering design process will consider how the operator needs to do their job in each mode.

This user input cannot be emphasized enough. Understanding workflows, business process, maintenance, field interactions, management and visitor interactions are elements that are documented before design begins. Interviews and workshops are necessary across operation teams to tease out the requirements that are generally not easily articulated.

Don’t reinvent the wheel

Usually companies design one new control building at a time, and although some consider modular design concepts, most designs are unique. Organizations used to applying more repeatable design processes struggle with the high cost associated with the one-off nature of control facility design. Clients are often looking for examples of how other organizations have designed similar buildings in an effort to take shortcuts to the design process. Although reviewing case studies and visiting control facility sites is highly recommended, copying a successful design for use with another company is not. Each client’s facility requires an independent analysis of how it operates and should be designed. Each company has unique operational priorities, and organizational and business processes that need to be integrated as part of the design process.

Although copying a design is not advised, there are documented standards used by control building architects to ensure that a comprehensive design methodology is applied. The most widely referenced is ISO 11064, which provides meticulous detail from the start of the process to the end.

ISO’s Principles for the Ergonomic Design of Control Centers include:

- Part 1—Principles for the design of control centers

- Part 2—Principles for the arrangement of control suites

- Part 3—Control room layout

- Part 4—Layout and dimensions of workstations

- Part 5—Displays and controls

- Part 6—Environmental requirements for control centers

- Part 7—Principles for the evaluation of control centers

Plan for change

We live in an era of unprecedented business and technology churn. A veritable tsunami of technology advances in displays, collaboration and communication tools, along with IIoT, cloud technologies and Big Data, are disrupting all industries. Designing a control building without considering the change that will inevitably occur over its useful lifecycle is another shortcut that is not advised. Preparation and planning need to be built into the operations facility from the start to ensure the facility can accommodate the future. Business growth may mean more operators, and business process changes may mean more analytic or engineering support for operations, both of which could require space to accommodate additional consoles, desks or other equipment in the facility. Consider the lifecycle expectation of this facility when deciding the size—don’t assume needs will remain constant.

Adding new technology, upgrading computers, monitors and peripherals needs to happen quickly and easily without operator disruption. A control facility with design features that allow easy access and maintenance may cost a few dollars more per square foot, but the savings in future maintenance costs will be well worth the investment.

The Red Box phenomenon

When a company decides to move ahead with an expansion project, these large projects—which likely include a process plant, equipment and associated support buildings—are often turned over to Engineering, Procurement and Construction (EPC) organizations. As their title suggests, these are often expert in building and implementing new industrial production projects. They typically have all engineering expertise in-house, including architects and designers for the various buildings inherent in these large projects. They may or may not have architects and designers with experience in designing control buildings. What is true of EPCs is that they are hired to deliver on time and on budget a large project, within which the control room or control building may be a very small component.

To streamline and accommodate an operations facility, an EPC will often quickly estimate the size of the space needed for operations based on a formulaic “number of heads” approach, then begin building the structure, or “red box.” The approach is a good methodology for estimating space in a general-purpose building, but it doesn’t address the standards and best-practices knowledge required to define the space for a proper operations control room and facility. The predefined dimensions of the red box are then used to insert a control building design into the structure. While there are scientific principles behind these dimension estimates, this is an attempt to shortcut good engineering design process for control buildings. In this scenario, instead of designing a building from the operator out, we are fitting a control room into a predesigned red box that often fails to take into account how the operation needs to function. Multi-floor spaces with low ceilings and multiple support columns are examples of what can be found in these boxes, and they can be detrimental to good control building design.

Don’t confuse software with design

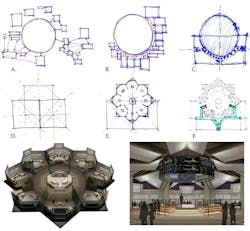

Software applications or virtual-reality renderings that can provide options of building design and console layouts are useful, but they can also be misleading, and should not be substituted for actual operator-centric design. Console locations and other room elements need to come after an understanding of how the operation needs to function, pursuant to human factors engineering and a workflow study. A well-designed control facility must meet the needs of the operation exactly and precisely, based on an iterative engineering design process (Figure 1). Software applications using algorithms for console layout and room dimensions (Figure 2) are powerful tools to assist in visualizing how a facility will look and feel, but represent another ill-advised shortcut to following a systematic engineering design process. The best, most functional control rooms arise from a collaborative approach where the client and designer work on improving the design through a process of multiple iterations of design ideas at the very beginning of the project. This ensures that the design meets the goals and objectives early in the process.

Figure 1: From concept through schematics, development and virtual renditions, control room design is an iterative process where expertise in engineering and architecture are devoted to satisfying production requirements.

Internal champion, external leader

Another common shortcut in the design process is to fail to find an internal leader to champion the project. Projects are often delayed and fail to be funded due to lack of an internal leader. Operational leaders can get projects started, but unless a senior leader emerges or is identified as the champion, projects can begin experiencing schedule delays and budget setbacks, then lose steam and internal support. It is recommended that the champion start the operation facility planning process with a benchmarking exercise, work with an experienced architect and designer, visit successful projects, and talk to other clients who understand the process and the level of engagement needed to succeed.

Figure 2: Applications using algorithms for console layout and room dimensions are powerful tools to assist in visualizing how a facility will look and feel, but an ill-advised shortcut to following a systematic engineering design process.

In addition to an internal champion, another common misstep in the design process is allowing ambiguity of leadership among the external vendors involved on the team. Leadership may come from the automation vendor when a major technology upgrade or change is planned along with the new building or renovation. This works best if the automation vendor also understands proper control room design process and has a working relationship with an experienced control room architect. Another leadership scenario involves the EPC project manager as leader for the control facility. With the right team, this can work well, but as mentioned earlier, the EPC’s goals and objectives differ from those of the control building architect, so it’s critical to ensure clear communication of expectations for the design process. An experienced control building architect is an ideal leader for the design process, because he or she understands the process and how best to achieve the required results. Regardless of which vendor leads the process, it is critical that the internal champion and the external leader have a close working relationship, and are aligned with goals and priorities on the project.

All or nothing? Sounds expensive

Designing or renovating a control building is often a once-in-a-generation project, and along with the functional design, there are also aesthetic considerations. Is the company expecting this to be a showcase facility, where dignitaries and guests will visit? Should the building project the company’s brand? Is the building intended to have facilities focused on employee comfort and retention? Designing a control building that addresses both the organization’s operational functional needs and aesthetic objectives is another reason to invest in an experienced control building architect. However, it does not have to be all or nothing—there is room for an incremental approach with respect to control building design.

Focusing on the early predesign and planning activities at the beginning of the design process with an experienced architect can help you document your operation’s philosophy and vision, understand current control room operations issues and gaps, develop your project priorities, estimate size, cost and schedule, build a roadmap, identify the team needed, and plan for change management in the process.

These early steps are critical to success, and cost a fraction of the overall control-building budget. They should be done as an incremental first step—to not only define the project, but to validate the credentials and working relationship of a potential control building architect. It is best to know early on that the architect you have hired is aligned with you and your organization.

Conclusion

Common business challenges for companies planning new control facilities include short timelines, high risk outcomes, scarce human resources, and high expectations for return on investment, to name a few. The search for areas to cut costs and save time and money is expected on all projects. The challenge is to balance that search without compromising proper control building design processes.

- Start planning early with an experienced control building architect

- Design from the operator outwards

- Apply ISO 11064 standards and best practices

- Expect growth and change in the design

- Don’t allow the control facility to be forced into a box

- Use software as a tool, not to replace good design

- Align internal champion and external leader to optimize the outcome

There is a cost to designing a control building the right way. Like any design process, the earlier changes are identified and implemented the less costly they will be. Shortcuts have a habit of showing up as issues later in the design process—and subsequently cost more to resolve.

About the authors

Brad A. Walker, architect, president and founding principal, BAW Architecture, can be reached at [email protected]. Peggy A. Hewitt, independent consultant and business development & marketing leader, BAW Architecture, can be reached at [email protected].

Latest from Asset Management

Leaders relevant to this article: