The Lowdown on Radar Level Measurement

By Walt Boyes, Editor in chief

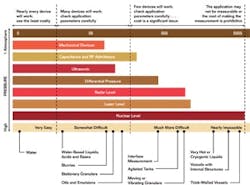

We have talked in this magazine about what I call the level measurement continuum before. Basically, there are level measurement applications that are very easy to do, and any level measurement device will work. There are also level measurement applications which are simply too hard to do with current technologies. Between easy and too hard to do, lay all the level measurement applications that require increasingly complex and costly measurement devices (Figure 1). [Editor's note: the chart detailing these level measurement concepts can be downloaded here.]

Figure 1: The Level Measurement Continuum

One of the "Okay to Use" bars in the chart that goes furthest toward "Too Hard to Do" is radar level measurement. It is one of the three measurement principles that can do the "really difficult" applications: radar, laser and nuclear level gauges. It is the one of the three with the widest applicability, and one of the most affordable measurement principles.Radar level measurement is basically divided into two groups, free-air and guided-wave. In free-air radar measurement (Figure 2), a signal is sent from a non-contacting device and received back at the device. Using either transit time or frequency modulation techniques, the distance from the device to the level is derived, and used to calculate the level of the liquid or solid being measured.

Figure 2. Using the distance between the device and the top level gives the level in the vessel.

Free-air radar works much better than ultrasonic level gauges and is significantly less costly than nuclear level gauges or laser level devices. It's substantially immune to vapor blanket variation in the vessel, to steam, dust and foam in the vessel, and can be easily removed for cleaning and calibration.Free-air radar solves many of the problems of difficult level measurement applications. You're able to mount the device in many existing vessels using an existing connection, which is normally 4 in. to 12 in. Vessel nozzles on many vessels are unused and available.

However, what happens if you have a vessel where there's extreme agitation, vessel internals, granular materials or extreme coating of the vessel side walls? These all reduce the ability of the radar level gauge to receive the return signal. In the case of transit-time, free-air radar, signal loss can be total. The dielectric constant of the material being measured matters too. If the dielectric is low and there are other issues, free-air radar may not work well, or it may not work at all.

For decades, we've been installing capacitance or RF admittance devices in tanks to measure level. These devices work very well—if they can be installed to miss internal structures, have appropriate materials of construction and the tank isn't agitated much, if at all. The physical design is well-suited for tank level measurement, and these devices can often be inserted through a tank nozzle much smaller than the ones necessary for free-air radar level measurement. The problem is that radar works on applications where capacitance or RF admittance devices do not.

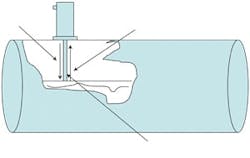

Enter a technology called time domain reflectometry (TDR). A probe, somewhat similar to an RF admittance probe in physical shape, is introduced into the vessel through a tank nozzle. Nozzles can be as small as 2 in. for this purpose. Generated pulses of microwave energy are transmitted down the probe. As soon as the energy pulse encounters a material, liquid or solid, that has a different dielectric constant from that of the vapor space in the vessel, a reflection is generated, and a return pulse travels back up the probe. The transmitter's circuitry creates the transmitted pulses, receives the reflected pulses, and uses the time differential between them to calculate the distance from the probe to the surface of the level to be measured. The difference between that measured distance and the bottom of the vessel is the actual level in the vessel. (Figure 3 shows a typical TDR setup.) Because the probe is used as a waveguide, the technology is usually called guided-wave radar.

Figure 3. Using a wave guide, the signal is sent down the probe and reflected back to the transmitter.

Guided-wave radar works very well in confined areas where the beam spread of an ultrasonic or a free-air radar level gauge does not. It also works with materials that are of a lower dielectric constant than a typical pulse radar unit, and its precision is comparable to many FMCW radar gauges. A typical range of dielectric constants for a guided-wave radar gauge is from about 1.5 to around 100. For many years, one of the vendors of guided-wave radar gauges, Magnetrol International, (www.magnetrol.com) has published a Technical Handbook that we host at ControlGlobal.com.One of the most useful sets of data in that handbook is the tables of dielectric constants for selected materials. That typical range of dielectrics covers a very large spectrum of materials from hydrocarbons to water-based liquids such as acids, bases and other industrial products. Because the wave guide probe can be cleaned in place, it is usually acceptable for service in tanks with food-grade liquids such as orange, apple or grape juice, as well as other water-based liquids.

Guided-wave radar gauges can also be used for interface measurements, such as oil and water, where the dielectric of the top level material is lower than the dielectric at the interface. Both levels send back reflections, and the gauge can be programmed to see the interface as well as the top level. Interface measurements between thick emulsions are not always good applications for guided-wave systems, and the introduction of steam into the vapor space can cause errors of on the order of 20% because of the high dielectric constant of the steam.

Guided-wave radar gauges can be installed in stilling wells to replace existing mechanical float or displacer gauges, and can generally retrofit existing capacitance probe applications quickly and easily.

Most guided-wave radar gauges have HART, Profibus or Foundation fieldbus outputs as well as the standard analog 4-20 mA DC output.

Guided-wave radar helps extend the performance line of radar level gauges in our Level Measurement Continuum chart.

For more on guided-wave radar level measurement, check out Greg McMillan and Stan Weiner's "Control Talk."