2018 Control Process Automation Hall of Fame - Part 1: Thomas McAvoy

Unlike in days of yore or in modern, but backward realms or quaint hierarchies, where crowns are inherited, bought or won by war or intimidation, new inductees to the Control Process Automation Hall of Fame are selected by their peers—the current, active members.

We say that Hall of Fame members stand out for three qualities: the extent of their process control knowledge, their wisdom in applying that knowledge, and their success in sharing it with others. It’s a good kind of fame.

Members nominate potential inductees, members vote for their choices among the nominees, and those votes determine each year’s new group. Our editors just facilitate the process by asking members for nominations, distributing the ballot, and tallying the results. This year’s ballot carried 14 nominations, a typical roster of extremely worthy candidates. Two stood out, and here are their stories.

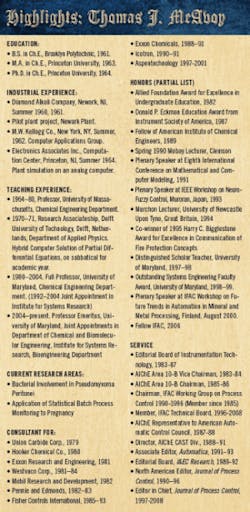

Professor Thomas McAvoy’s odyssey into our Hall of Fame began in graduate school at Princeton, where his thesis research under Ernest Johnson was in process control. As an undergraduate in chemical engineering at Brooklyn Polytechnic Institute, he’d held jobs at the Diamond Alkali Company in Newark, and at M.W. Kellogg in New York, in a computer applications group. While at Princeton, he worked in the computations center at Electronics Associates.

“I always liked application as opposed to theory,” McAvoy says, and as he neared graduation, he decided his calling was to be a teacher. “This turned out to be one of the best decisions of my lifetime,” McAvoy wrote in his 2016 book, Science Deepens Faith: Jesse’s Miracle. “In 1964, there was a very large (and negative) salary differential between academia and the chemical industry, and some people thought I was a bit crazy not to go into industry; but eventually, academic jobs became much more attractive.”

Teaching, in various contexts and around the world, became McAvoy’s hallmark. At the age of 24, he became the sixth faculty member of the chemical engineering department at the University of Massachusetts (UMass), Amherst, which had just gained permission to award PhDs. During the 1960s and 1970s as a professor at UMass, then in the 1980s and 1990s at the University of Maryland, he worked with hundreds of PhD candidates, dozens of companies and numerous organizations to spread understanding and to improve process control.

While at UMass, he helped teach an industry seminar on distillation control. “Ed Bristol and Greg Shinsky offered great insights and used to bring students,” McAvoy says. “I did a lot of work on Ed’s relative gain array.”

Thomas McAvoy says, “I love to go fishing.” Here he displays a 45-in. striped bass caught near his son's house on the eastern shore of Maryland.

Bill Luyden was teaching short courses at Lehigh. McAvoy lectured there, then started running them every two years at Maryland. “We had about 35 people from industry—DuPont, Exxon and so on. Karl Ǻström and others would teach as guest lecturers.”McAvoy is proud of his work on distillation, and on the relative gain array with Bristol, “But, I think my most important work in process control was on neural networks with students in the 1990s,” McAvoy says. “I worked to set up an industrial consortium, which at one point had 23 companies as members. Since then, Joe Chen at USC has combined statistical analysis with neural networks in works that have been cited hundreds of times.”

McAvoy took a number of sabbatical leaves both in industry and academia, including in Exxon’s artificial intelligence group, DuPont’s experiment station, and Fisher Controls in Austin. Academic sabbaticals included Delft University, Holland, in hybrid computers, and USC Medical School in biomedical applications. He found medical applications of control theory to be quite interesting. “Once you have a model, you can turn it around and know how to do dosing,” he says.

Around 2001, McAvoy and his wife started planning to retire, but in 2003, she was diagnosed with a rare cancer, pseudomyxoma peritonei (PMP). The disease took her life in 2004.

McAvoy devoted time to researching PMP. “We hypothesized a bacterial component,” he says. “I allied with a surgeon and we started research group that’s still going on after almost 14 years. If anyone told me back then it would still be going on, it would have amazed me. For a rare disease, it’s hard to get funding, but the bacterial component is interesting. More cancers seem to have one.”

Future of the profession

McAvoy sees automation as “a mature field,” he says. “The hardware keeps getting better, such as wireless and memory. I think artificial intelligence may be being a bit oversold.”

For the future of our workforce, he says, “The system rewards students for going into management, not science or engineering. In our graduate programs, most of the students are foreign students. They’re better at math and sciences than U.S. students. I don’t think high schools are as good as when I came up.

"The universities themselves are cutting back the requirements. At UMass, to be kinder, we ‘phased’ students 1 to 5 instead of grading them F to A. At Maryland, a degree that used to take 144 credits can now be done with 128 or 124.”

Asked if he would do the same things if he were doing his life over, McAvoy says, “The next century will be the century of biology."

For example, in our PMP research into the microbiome of tumors, tests that used to cost $3,000 now cost $100. It’s like comparing the Wright brothers to a 747.

“Will biological applications cross into process control? I would be looking at biology and medical applications.”

McAvoy has two sons and a daughter. Though all are doing well, none have chosen to follow in his footsteps. “My daughter is in business,” he says. “One son started college in civil engineering, but decided to get a degree in art. He’s now in web design and programming. The other is in business and has his own company, working with clients in the DoD and state department.”

Based on his observations of his progeny and students, “It’s possible to specialize too soon,” McAvoy says. “Chem E students have better backgrounds than students who specialize in, say, biomedical. Those need an MS to get a job in the field.

“Chem E is great for a lot of things. An environmental engineer is mostly civil engineering, but it restricts your options. Get a good, basic degree, then if you want, you can go into med school or something else.”

McAvoy has since remarried, and has an extended blended family. He says, “With my own nine grandchildren, when they’re making the decision, my advice is, consider biology!”