Process Automation Generations Talk to Each Other

Greg McMillan is a Control columnist. Danaca Jordan is a manufacturing staff engineer for a specialty chemical company. Hunter Vegas is senior project manager at Avid Solutions Inc., and Soundar Ramchandran is senior director of technology for Ascend Performance Materials.

To add insult to injury, many of the books I consider my core knowledge are now out of print. To avoid a relegation of innovation in the automation profession to moving and manipulating data, we need to find out how to nurture and expand control expertise by better communication between generations. More specifically, how do we help the new generation of automation engineers benefit from the legacy and move the profession forward?

While some may say control technology is mature, I take the view the flexibility and power of modern day software opens up vast opportunities for creativity. We can take process control to the next level if we can address many questions. How can we take full advantage of what has been learned? Will people be given the time to explore new possibilities and the freedom to publish the knowledge gained? Will a supplier or a user ever again support a person like me? Will there ever be another Shinskey?

To get a view from each generation I posed key questions to Danaca Jordan, manufacturing staff engineer for a specialty chemical company, Hunter Vegas, senior project manager at Avid Solutions Inc., and Soundar Ramchandran, senior director of technology for Ascend Performance Materials. Each of these participants in the ISA Mentor Program has extraordinary technical and communication skills.

Answers by Danaca Jordan (Gen Y), Hunter Vegas (Gen X) and Soundar Ramchandran (Boomer)

Greg: What can each generation learn from the other generation in terms of communication and solving problems on the job?

Danaca: My generation needs to focus, realize communication has consequences and do more effective networking. Here are some things we need to learn and should try to share:

Multi-tasking is a part our generation's culture, and it can have positive effects, such as the ability to recover from interruptions quickly and extreme adaptability, but sometimes I lack the focus I see in other generations. I am guilty of checking email during meetings, browsing during teleconferences and having multiple IM sessions (internal company messages, of course) active while I'm trying to work on something that really deserves my full attention. We have more ways than ever to procrastinate and distract ourselves, and if we are not mindful, it will affect our productivity.

I often rely on artificial means, such as work timers and browser-time-out apps (StayFocusd, for instance) to really home in on more daunting tasks. I also disable Outlook pop-ups, most notifications and set my phone and Lync communicator to Do Not Disturb when I truly need to buckle down. I have learned recognize when I need to disengage from all of the technological noise, or I may end up staying late to finish a vital task after losing an hour to Wikipedia.

Another topic we could learn from others is the consequences of communication. Other generations tend to think we are naïve when it comes to the information that we share online, and I agree that we should try to learn from their mistakes. We have all heard the litany about posting photos or personal information that may damage your reputation, and many programs now offer improved anonymity or privacy settings to combat this. Profiles aren't the only way to slip up, however.

Through the examples of others, I have learned that written and verbal messages can and will be saved or forwarded to people you did not intend to include. The angry email you sent yesterday could end up hurting your credibility with a customer or your employer. In tense situations, I have made a habit of saving emails for the next day and often end up deleting or completely rewriting them.

A point here for all generations is that anything posted online is no longer under your control, including comments that could reflect badly on you or your company.

Finally, online networking is for more than just job-hunting. We have global virtual communities set up for almost everything that we do, like or support. There are forums for specific software and instrument user groups, archives of shared code and open edit wikis on thousands of topics. People all over the globe share stories in these forums about how specific products worked, what problems they encountered and how they overcame them without giving specific details of their plant's operation. Someone somewhere in the world is having the same issue you are, and we now have tools in place to discuss solutions without spending time or money on conferences and meetings. Newer engineers can ask questions with some anonymity, and veteran practitioners have a way to quickly share their experience and thoughts outside of formal journals and company reports.

During an internship, this easy access to information almost caused a misunderstanding with my supervisor, who came to me concerned that I was not asking enough questions about a new project. Just as we now use a global positioning system (GPS) instead of asking for directions, I did not want to seem ignorant of the topic, so I went online for all my answers. I have since learned that I am not supposed to be omnipotent. Plant staff has years of detail on the specific plant history and what has and hasn't worked over the years, so I tap multiple sources for information.

Hunter: Before I answer any of these questions let me start by saying that I am not a big fan of creating generational "labels" and trying to force fit a large group of people into a simplistic box. Every engineer is different; each is motivated by his own particular set of personal experiences and many take some offence when they are lumped into a generic group which may not have any relevance or similarity to them at all.

To that end I will tend to frame my answers by referring to "younger/less experienced" engineers and "older/more seasoned" engineers. Of course, younger and older is all relative, but I have found this reference to be much more useful than grouping engineers by their year of birth.

Communication is critical to the success of any project regardless of the age group involved. So many intergenerational problems balloon out of control when one group stops talking/listening to the other. I have watched older engineers dismiss great ideas from younger engineers because they had not thought of it themselves, or they were unfamiliar with the technology. I have watched younger engineers stumble and fail because they thought they knew it all and were too proud to ask for help. (To be honest I have probably been guilty of both at various times in my career!)

Open channels of communication allow all age groups to propose ideas and have those ideas fairly and completely evaluated. If an idea has merit, then it will get implemented. If the idea has problems and is discarded, then everyone understands why and learns from it. Talking things out before action is taken gets everyone on board and lets the group take advantage of everyone's talents.

Much has been written about the types of communication used by older and younger generations. Younger engineers often rely on texting, tweets, blogs and the like, while older engineers tend to gravitate to more formal written information. Personally I have found that the most effective communication is a face-to-face conversation. I derive as much (or more) information from the visual cues, body language and voice inflection than I do from the words themselves. Tweets, texts, emails and memos are fine, but if you truly want to communicate with another person, then there is nothing better than doing it in person.

Soundar: While realizing generalization is subject to individual experience and uniqueness, free will and adaptation in the human response, the recognition of the generational differences can help us understand some of the behavior at play in communication. Statistical methods can confirm these tendencies.

Baby Boomers (1946 to 1964) are characterized by hard work, positive attitude and a general sense that the world will get better with time. Most people were physically fit, and life was not lived in excess. There was a strong correlation between working hard and becoming wealthy. Work was seen as the reliable means to become financially independent, and there were many examples of this around common friends and social circles in many neighborhoods. Boomers have self-confidence and trust authority. They want a prestigious title and a corner office. They respected their parents because they were controlled and indulged as children. Education for them was a freedom of expression. The key question Boomer asks is "What does it mean?"

Generation X (1960 to 1984) – This was a period of awakening for many. There were dramatic contrasts in individual choices and opinions on wide-ranging topics (for example, the Vietnam war, Nixon, Iran hostage crisis, Ronald Reagan, Berlin Wall, Chernobyl, ending of Cold War, AIDS, MTV, etc.) that spanned the whole gamut from drug use, dysfunctional families, domestic violence and school bullying to embracing social diversity, religion, ethnicity and sexual orientation. It was a time of extremes. This generation displays a low level of trust towards authority. They want to have the freedom to not to have to perform meaningless tasks that lead to nowhere. They dislike commercialism, restriction of individuality, the mind-numbing corporate monochrome culture, etc. They tended to more pragmatic and focus more on self-awareness. The key question that Generation X asks is "Does it work?"

Generation Y (1977 to 1994) is incredibly sophisticated technologically and immune to most traditional forms of marketing and sales pitches. They are more racially and ethnically diverse from the previous generation. They grew up in the world of cable TV, satellite radios, Internet, and e-magazines, etc. They tend to be very flexible and fast to change. They expect to be successful in whatever they do and are very competitive and driven, which sometimes gets viewed as having the potential to be rebellious. They have a high level of trust towards authority, but at the same time they are less trusting of individuals. They prefer meaningful work. Members of Generation Y are definite about parenthood and view marriage and parenthood as more important than their careers and success. They seek protection as they were protected as children and, therefore, need a structure of accountability. They crave community and care for the group as a whole, as opposed to themselves. The key question that the Millennials want the answer to is "How do we build it?"

Recognizing the core strengths of every generation, we can benefit from each other by recognizing and learning:

- From Boomers, the positive and upbeat attitude and to ask "why" and "how," enough times to get to the root cause of something;

- From Generation X to become self-aware, focus on individual strengths and weaknesses, and figure out how we can work as a team to deliver great results;

- From the Millennials, the speed of adaptation, opening our minds to new ideas and new ways of looking at things, and using the new tools being developed to take advantage of the power of electronic means of communication.

Greg: What are the biggest challenges faced and potential improvements in terms of getting the right information that is timely and useful?

Danaca: There are several key issues involved in sorting through and finding helpful information quickly. The foremost concern is information overload. When first looking into a subject, the sheer volume of information that has been written is overwhelming. Journals, books, blogs and papers are scattered across the Web and mixed with biased marketing literature. Much of the educational literature is not online or searchable, so can be accessed only through hard copy. Finally, from a normal Google search, it is difficult to determine if a paper or book is still viable. Is this instrument still the best for liquid service; is this rule of thumb good for newer column trays?

The surest way to combat the overload is with a mentor. A knowledgeable mentor will help narrow down the mass volume of information by suggesting an author or article for various topics.

Without strong mentor programs in place, we lean on wikis and online recommendations to point us in the right direction. In a solid entry or blog, authors will give overviews of a topic with links and citations to peer-reviewed articles and books. Open editing and commenting reveals or prevents biases. I often think that this kind of system would be wonderful for an internal company knowledge base. We could add our technical reports, discuss comments and questions, and share ideas between isolated sites and corporate engineering without formal meetings, conference call-in codes, or cost center charges.

Hunter: There are a couple of key concepts that, if understood and applied, would have an enormous positive impact in the engineering workplace of today. These are

- Many "new" technologies are rebranded/repackaged "old" technologies.

- Some new technologies are new and can be transformational.

- Change is not always good.

- Change is not always bad.

It is an odd mix, but each concept has very different meanings to different age groups.

- Many "new" technologies are rebranded/repackaged "old" technologies – Despite what one reads in the latest marketing brochures, most "new" technologies are not new at all. They are reincarnated versions of an old technology that has probably been around for years. Often the performance of the device is somewhat limited by the physics of the sensor technology, so it will often fail and/or succeed much as it did when it was released years ago. This is where more experienced engineers can offer a great deal of insight when evaluating these "new" technologies. Is it new or is it just re-introduced? Why did it fail before? Has that issue been addressed and/or resolved? Adding a glitzy computerized front end may make the device look impressive, but it may not work any better than it did when it came out years ago.

- Some new technologies are new and can be transformational. – Occasionally a new technology hits the market that is new and works an order of magnitude better than any competing offering. If such a technology presents itself, an engineer would be foolish not to take advantage of it. This is where younger engineers tend to shine, as they generally follow the latest trends and are more knowledgeable on the most recent offerings. However, just because a new product looks good does not mean that it will actually work. A more experienced engineer will tend to be more cautious when implementing such a technology to be certain it delivers all that it promises. (That caution is usually the result of several past instances where the "best thing since sliced bread" was not all it was purported to be.)

- Change is not always good – Younger engineers are used to a constantly changing world and tend to be more comfortable with an atmosphere of continuous change. Unfortunately, change for change's sake is not always a good thing. There may be a sound reason why the plant has "always done it that way," and just because the current technology is old does not mean that it isn't the best solution available. (There are still situations in industry where a pneumatic transmitter is absolutely the best choice!) New is not necessarily better, and a low tech, reliable solution will often outperform the "latest and greatest" product in many situations.

- Change is not always bad – Older engineers tend to stick with the tried and true. If it works, why mess with it? However, that reluctance to try new things will often make them miss out on transformational technologies that can generate dramatic improvements in productivity and reliability. Even harder for an older engineer is the decision to give a particular technology another try after it has failed before. Consider electronic transmitters. Early adopters had all kinds of problems with reliability and performance when they installed the first generations of electronic transmitters. In some cases, hundreds of transmitters were pulled from service and replaced with pneumatics. After such an epic failure, I have no doubt that it was very difficult to give the technology a second chance, but clearly the electronic transmitter concept was worth pursuing once the bugs and problems had been resolved.

The point of my answer is that both young and older engineers have much to offer each other if they open their minds and hear what the other group has to say. Older engineers should listen to younger engineers and try out their ideas when they present them. Younger engineers should listen to the older engineers and understand the history of why certain equipment and/or procedures are being used. Each has information the other desperately needs.

Soundar: The questions that need to be answered in terms of doing a better job in process control for improving existing systems as well as executing new projects in a timely and useful are these:

- What is it that we are trying to accomplish?

- How will it impact the bottom line?

- When and how will the impact be realized?

- Why is it important to do this?

The biggest challenge I see is that most of the time we start the dialog with the "Why is it important to do something" question. While it is important to know the answer to this question in a deep and fundamental sense, it becomes a distraction, as the conclusion and recommendation is not obvious in the "why." Working the details of any problem should lead to a conclusion or a recommendation. It is the conclusion or recommendation, the ultimate result from the scientific analysis, which is more important than the mechanics of analysis itself. Most of us miss this and get mired in "teaching the science" to the decision-makers. This is the fundamental reason for failure of many communications; it fails to achieve the desired outcome and leaves both parties disappointed.

Greg: What are some key mutually beneficial features of a mentoring program that could be set up within a plant or company?

Danaca: The first hurdle for any mentoring program is setting expectations for the parties involved. Time is extremely valuable to both parties, and agreed-upon rules for when and how to communicate, formality, timeframe and goals is key to ensuring that neither party's time is squandered. I would be frustrated with a mentor who never returned emails, just as some mentors would prefer to hold scheduled sessions with predetermined agendas.

A great mentoring program will involve peer mentoring as well as more traditional cross-generation relationships. Peers are great sounding boards, often have similar issues and are easier to approach than the esteemed experts in the field. As demonstrated during my ISA mentorship, mentoring a group of peers together can foster this interaction, as we now have shared experiences and known interests. For example, I know I can go to my fellow Hector for questions on using advanced PID features and only involve our mentor as needed.

Hunter: It has been my experience that the best mentoring relationships occur when the engineers work together as part of a team, rather than setting up a formal program where an engineering new hire meets with his mentor on an intermittent basis. Engineers learn by doing, and if a younger and an older engineer work together, there is much more opportunity for the young engineer to see and understand the hundreds of design decisions that must be made during a project. At the same time, the older engineer is developing a valuable team member who can contribute to the success of the project. Formal mentoring programs are okay, but I would strongly suggest that, if at all possible, the company try to pair older and younger engineers together in a working relationship.

Soundar: A mentoring program within a plant or a company should focus on educating and coaching how to make the upcoming generations successful. Newer generations need coaching on how to sell their ideas and thoughts to their supervisors and leaders. As corporations tend to be hierarchical like family structures, it is more than likely that a majority of the leaders may be from a previous generation. In a typical corporate or plant structure today, it is highly likely that the president and his staff and the senior management will be from the Boomer generation, whereas the middle management has a greater percentage of Gen X and the first-line leaders, and their staff comprises of mostly Millennials.

Exposing the Millennials to the way of thinking and value system of the Boomers and Gen X would increase the ability for all of these generations to understand each other better and enable companies to benefit from the new ideas and technological innovations that are happening in the present time. Empowering Millennials will produce innovative solutions to problems that were once considered as "cost of doing business."

Mentoring is a two-way street; both the protégé and mentor have to be invested. The mentor sees value for the time they spend on the protégé, and protégé should take advantage of the opportunity as a means to gain valuable knowledge from the experience that someone is willing to share. I have found that experience is the hardest thing to explain to a younger generation. In as much as we say that the value system changes from generation to generation, I find that the difference is only in the dynamics of the response. The steady-state gain for the values has not changed much from generation to generation.

Greg: What are some ways of gaining recognition and advancement besides doing your job well?

Danaca: From what I read and see at my office, this is one of the larger areas of misunderstanding between generations. Millennials like me are often labeled as entitled because we tend to expect immediate feedback on our efforts. Some experts propose that our parents caused this by praising our every accomplishment, including just participation. I doubt that was the only influence, but since I am an engineer rather than a social scientist, I will not attempt to explain how these tendencies started. I will say that we are perpetuating the trend long after we move out.

The extent of social media use may be responsible for some of the disconnect between generations here and elsewhere. On Reddit, for example, a user can post a picture, story, news piece or observation. It is immediately up or down voted by the community. In addition, other users can comment on the submission, and the comments receive ratings. Even sub-comments about the original comments are voted on, with only the best rising to the ephemeral Front Page. If something is ignored, it soon disappears. People will spend hours working or risk limbs for a brief acknowledgement with no thought of money or reward.

Based on this, I believe that cheap, short-term recognition is much more effective for my generation than an expensive carrot at the end of a long stick. Offering long-term promotions or money is always welcome, but I would appreciate feedback, good or bad, on a very consistent basis. A simple "Thanks" or "This is what I am looking for," or even "Not quite, can you add…" will motivate my efforts, whereas if a project or document is ignored, I assume it was not important and try to work on something worthwhile instead.

Hunter: I would strongly encourage engineers to give presentations at technical forums and write articles and/or technical white papers whenever possible. Volunteer to talk at your next ISA meeting. Such activities allow engineers to be recognized outside of their companies, and such positive recognition is often reflected in promotions and monetary rewards within the company as well.

You did not ask this question, but I will offer one other piece of advice to younger engineers. One of the most difficult situations for a younger engineer occurs when that engineer is promoted over several older engineers. The older engineers often feel that they have been denied a promotion that they deserved, and they are concerned the younger manager will not appreciate their knowledge or experience and try to tell them how to do their jobs. The younger manager wants to make a good impression and show the new direct reports that he/she knows their stuff and deserves the managerial position. This is a recipe for disaster.

If you are ever faced with this situation, it is important to understand the dynamics that are afoot and address them carefully. Engineers of any age want to be a part of the decision-making process and feel that they are heard. They also want to be treated fairly. The new manager must ultimately make the final decision, but if the manager takes the time to elicit the opinions of his or her direct reports and incorporate that information into the final decision, then the initial concerns will often be eased. The best situation occurs when the manager and his reports have mutual respect for each other.

Soundar: Reward and recognition is different for each generation. It is not something we have quite figured out in corporate America. The basis for reward and recognition is still based on merit raises, special awards, bonuses, promotions, etc. The reward system has to be tied to the value system for each generation. For example, for Millennials, being offered a couple of baseball game tickets this week as a recognition for doing something good last week is more satisfying than being given a bigger bonus or higher percentage increase once a year. They live in a fast-paced world, and prompt feedback and affirmation is a critical element for them.

On the other hand, Gen X, while still accepting the baseball tickets would like to be remembered with a bigger merit raise or bonus package in the annual cycle. If the baseball tickets were the only thing they got, they would find it to be very trite. Boomers like promotions and other forms of recognition such as a bigger office or an office with a door, as a way of recognition for their hard work and successes. We have to learn to use all of the above and not get stuck on one form or another. It behooves supervisors to learn what is important to each generation as they figure out a way to lead their teams. Since more and more Millennials are finding themselves with first-line supervision roles, it is fitting that they also learn about values as perceived by the various generations as they may well find a few Boomers and Gen X on their team. It is very essential that they try to learn the value system and base the rewards and recognition in keeping with that value system if they want to have a winning team.

See the online version for the views by Danaca, Hunter, and Soundar on the relative effectiveness of different types of communication, visuals and levels of information.

Relative Ratings of Ways to Learn and Share

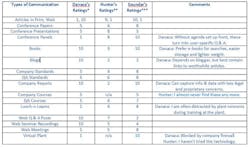

Boomers, Gen X-ers and Millennials not only have different ways of working, communicating and interacting with one another, they also have different ways of learning. We have asked Danaca, Hunter and Soundar to rate the material, methods and techniques for learning. What follows are their ratings and comments.

The ratings for communication largely reflect generational differences. The ratings for visuals and to, some degree, for levels of communication appear to be the result of the differences in the jobs. Hunter is focused on what is needed for project execution as a project manager. Danaca is interested in what helps a new engineer gain general knowledge to support and improve automation systems in a plant as a manufacturing staff engineer. Soundar, as a technology director, is thinking about what will help advance process control applications in the plants of a progressive chemical company.

Effectiveness of Types of Communication

Ratings are on a scale of 1 to 10 where a 10 denotes "most effective."

General comment by Greg: The virtual plant is an actual download of the configuration and operator displays connected to a process simulation running in real time. I have the used the virtual plant or predecessor (emulated plant runs) throughout my 40+ years to study dynamics and develop and prototype process control improvements. Most of my knowledge was gained from this exploration. The use of process control labs I created as a virtual plant for access over the Internet referenced by Danaca was blocked by company firewalls. The Process Control Labs Download can be imported into a lap top with virtual plant software where the user has administrative privilege and at least 4 GB of memory.

* General comment by Danaca: Other communication types not mentioned that I use frequently:

Online Forums – There are several DCS and instrumentation user forums, as well as online groups on networking sites that discuss common installations and troubleshooting. I use them to determine if someone else has seen the same problem that I have while remaining relatively anonymous.

Peer-Reviewed Wikis – Wikis are used as a starting point for most research and new projects. They provide solid overviews and links to standards, conference papers and journals for verification and more detail.

Social Media Feeds – I use these less frequently, but if managed correctly, they are an effective way to summarize and lead users to interesting or new developments. ChEnected, the online community for AIChE, provides a consistent example of timely, user-driven content.

** General comment by Hunter: I personally don't spend much time on the Web, so blogs, Q/A posts and recorded seminars are not something I tend to check out. I much prefer written material that I can read and digest. I tend to like live presentations where I can ask questions and better understand the material.

***General comment by Soundar: I find reading on a computer screen distracting, so any kind of learning for me has to be from something I can hold and write on.

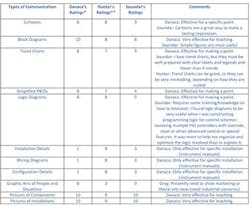

Relative Effectiveness of Visuals

* General comment by Danaca: Other visuals not mentioned that are very effective (10 rating) are animations and YouTube or other online demonstrations.

** General comment by Hunter: To be honest, I struggled with this one. I need whatever visual effect makes sense. For understanding the process, then a PID and/or PFD is what I need. If I am designing software, then I typically use a combination of flow charts, written logic notes and a tag list. If I am wiring something, then I want to loop sheet. My ratings numbers are a measure of how useful I generally find these items.

Relative Effectiveness of Levels of Information

Conclusion

The most effective way to share knowledge about the implementation of process control is networking by virtual communities, such as forums for specific software and instrument user groups, archives of shared code and open-edit wikis. Technical societies should correspondingly foster virtual committees for standards and advancing technology that is not supplier-specific.

Mentoring is best done by assigning experienced engineers to work with new engineers for implementing new systems and maintaining and improving existing installations. An open-door culture should be created where new engineers are encouraged to seek advice on a casual basis and good listening practices are fostered. One-on-one conversation is the most complete and beneficial type of communication to resolve misunderstandings and conflicts. All other types can escalate problems.

The ISA Mentor program found that questions and answers of general interest can be effectively conducted by email and shared by posts. Words cannot convey the enthusiasm and immediate bonds of mutual interest and respect seen in the kick-off meeting at ISA Automation Week. Conversations between protégés have continued to show the potential benefit of new automation engineers sharing and learning on a one-on-one basis. Finally, the co-authoring of articles, papers and presentations helped focus achievements, gain recognition and provided a greatly needed new user perspective.

Books, papers and articles are still the most effective way to transfer general knowledge. Print versions need to be available for the older generations who do not want to read on a computer screen and want the ability to creatively browse without knowing exactly what to look for. Web versions are increasingly important to enable longer versions, addendums, updates and internal/external searches.

Since presentations now have a life on the Web beyond the session, we should move beyond the concept of the content on slides serving just as trigger. Presentations and publications should have a synergistic relationship using layers to provide a progression of knowledge. The presentation provides the entry to more extensive knowledge via a publication. The layering of content in presentations and publications should be based on the ratings of visuals and levels of information for the audience. Successive pages or slides or links could give access to deeper layers. The layers can be added to Web versions as knowledge is gained and as time permits. For presentations, content must be brief with a minimum font size and a maximum word limit on each slide. Probably only the first few layers would be used in a presentation except when examples are given of what is available on the web version.

Successive layers with more information would be relegated to publications tied to the presentation. Here are the layers.

- Memorable Picture, Graphics or Cartoon to capture attention and open the mind.

- Overview to provide a high-level view.

- What, When, Why and Where to give value and applicability.

- Concept to capture the essence and give the basis for verification via scientific method.

- Insight to offer deeper knowledge that can expand applicability and spawn discovery.

- Simplified P&IDs and Logic Diagrams to provide a fuller understanding.

- Background to provide a perspective that can lead to additional ideas.

- Watch-outs and Exceptions to keep the user out of trouble.

- Rules of Thumb to provide guidance and to start the move from generalities to specifics.

- Checklists to make sure all the bases are covered.

- Details that govern the proper use.

- Step-by-Step Procedures to provide the literal instruction on what to do.