The IEEE P1451.4 transducer electronic datasheet (TEDS) standard will fundamentally change sensor production and use. The standard will allow vendors to embed calibration and scaling information on an EEPROM within a sensor. This information will be written to the EEPROM in a standard format for universal recognition by signal conditioners, standalone controllers, and PC-based data acquisition systems.

Sensors for load, pressure, torque, temperature, force, vibration, displacement, and other uses will be affected by this standard. Some manufacturers already include calibration information in their load cells, but this information is only available when using signal conditioning equipment purchased from the same vendor. TEDS will provide a universal standard and allow users to mix sensors and signal conditioners from different vendors.

TEDS sensors will include serial digital links for accessing calibration and other data, as well as analog signals for backwards compatibility with traditional measurement systems, according to David Potter, National Instruments' DAQ platform manager and vice-chair of the IEEE P1451.4 committee.

To see the potential benefits of this standard, it is instructive to examine life before TEDS. Most sensors are shipped with a paper calibration sheet. The end user manually enters calibration data from the sheet into the signal conditioning system. The calibration sheet is then stored for future reference.

A TEDS sensor arrives with all calibration data on its EEPROM. This data can be automatically accessed by any TEDS-capable signal conditioning component. Per Martin Armson, the marketing director of Honeywell Sensotec (www.sensotec.com), TEDS can also simplify labeling, cabling problems, and inventory control by letting a user burn location data onto the EEPROM.

Although TEDS has myriad benefits, users must consider several factors before implementation. Teaming sensors from one manufacturer with appropriate signal conditioners from another will be possible as long as the connection plugs fit. The standard does not specify connector types or pin configuration. It may therefore be necessary to sort out pins and change plugs before TEDS can play.

The IEEE 1451 Committee is considering addressing connectors and pin configurations, but in the meantime it may be better to specify flying leads on sensors and a terminal block on signal conditioners.

Signal conditioner manufacturers can choose to implement TEDS actively or passively. In an active implementation, the signal conditioner not only interrogates the EEPROM but also automatically adjusts its own electronics. In a passive implementation, it is necessary to tell the signal conditioning system what to do with the TEDS information.

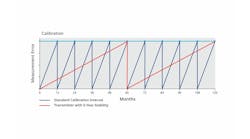

Sensor manufacturers generally consider calibration data to be accurate for one year before recalibration is needed. Once a sensor is recalibrated, the onboard factory-calibrated TEDS is no longer accurate.

But the industry has already devised a solution"the TEDS burner. If you send a sensor back to the manufacturer for recalibration, they will reburn the TEDS data sheet to make sure it carries the latest calibration data. Some calibration shops already are offering this service, and users can also reburn their own TEDS.

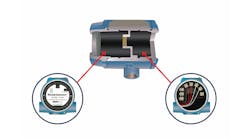

Legacy sensors can be upgraded to the standard by adding TEDS EEPROMs to them. Sensotec provides a kit to mount the EEPROM in the connector, in the sensor itself (the sensor is cut apart and rewelded), or in a special adapter attached to the sensor cable.

For those whose systems are PC-enabled, National Instruments has developed the concept of Virtual TEDS, whereby sensor calibration data is downloaded directly to a signal conditioning system. The company is becoming a clearinghouse for TEDS by gathering calibration data from many sensor manufacturers and posting it on the NI web site.

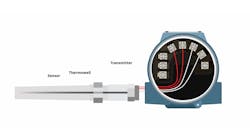

TEDS also can benefit users indirectly, because TEDS simplifies sensor production. The old way of manufacturing thermocouples and other sensors went something like this: Pick an existing standard (type K for example), try to make a thermocouple that meets the standard, and test all manufactured thermocouples for compliance with the standard. Throw away the ones that don't work, and sell the ones that closely (but never exactly) match the standard.

The new way of manufacturing thermocouples and other sensors will follow a different roadmap. "Vendors can pick inexpensive and rugged materials that exhibit high long-term stability instead of being forced to rely on materials defined in standards. They can test the finished products and embed the exact calibration and scaling information in the TEDS EEPROM," says William Schuh, a scientist with Watlow (www.watlow.com).

This is obviously a better way to make sensors, but what's in it for the end user? Better accuracy, because the sensor now exactly conforms to its own fully customized standard. Better long-term stability because manufacturers will be able to select stable materials instead of materials that can be manufactured to consistent standards.

And lower costs because manufacturers compete, and when they all adapt a lower-cost method of production and test along with lower-cost materials, then lower prices certainly will follow.